Gen Z really does have a work ethic problem

Or maybe we all do?

Older people often complain that the younger generation lacks a strong work ethic. Of course, it’s entirely possible older people have forgotten how lazy or unmotivated they were when they were young themselves. Polls or one-time surveys don’t help much, since we can’t tell whether any differences are due to age or to generation.

To get around these issues, we’d want self-report data from young people that we can compare across decades. This is what many managers, public policy experts, and parents want to know: Are today’s young people truly less willing to work than previous generations were?

In other words, what was each generation’s work ethic like when they were young? Nationally representative surveys like Monitoring the Future can show us this – it has asked U.S. 12th graders, most of whom are 18 years old, about their work attitudes since 1976. The 2022 data from this survey was just publicly released, so we can get a fairly up-to-date look at young people’s attitudes.

Up until a few years ago, the work ethic news was positive for Gen Z (those born 1995-2012, and 18 years old 2013-2030). After declining from Boomers to Millennials, work ethic made a comeback among Gen Z 18-year-olds in the 2010s.

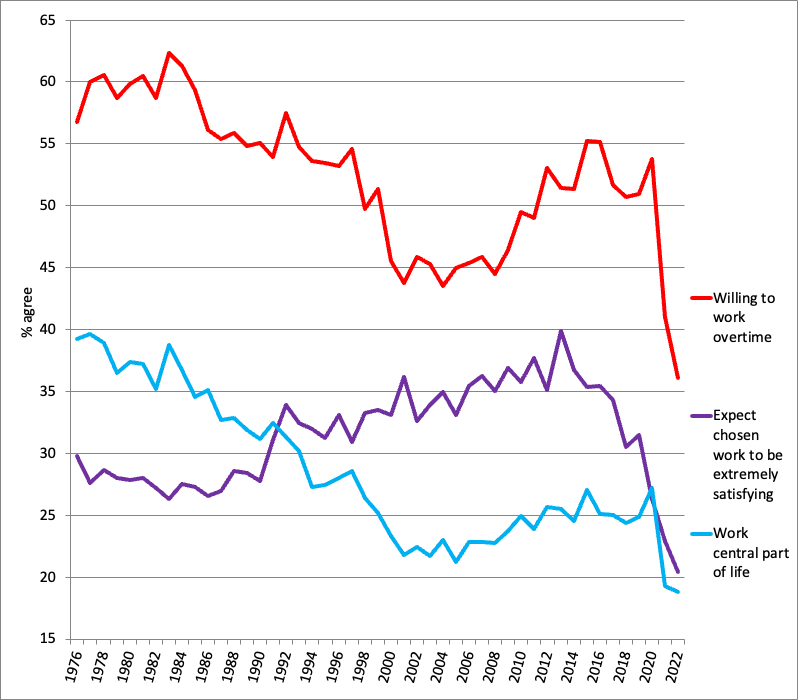

Until it didn’t. The number of 18-year-olds who said they wanted to do their best in their job “even if this sometimes means working overtime” suddenly plummeted in 2021 and 2022 (see Figure 1). In early 2020, 54% of 18-year-olds said they were willing to work overtime. By 2022, it was 36%. That’s a (relative) drop of 33% in just two years. It’s also an all-time low in the 46-year history of the survey.

Apparently, all of those TikToks about quiet quitting in 2022 were onto something.

Figure 1: Work centrality, U.S. 12th graders, 1976-2022. Source: Monitoring the Future. Similar to Figure 8.1 in the “Future of Work” section of the Future chapter of Generations

Another item asks an intriguing question: “If you were to get enough money to live as comfortably as you’d like for the rest of your life, would you want to work?” This item measures intrinsic motivation to work apart from the extrinsic need to earn a living.

The pattern here is similar to that for wanting to work overtime: A decline in wanting to work between the Boomers and Millennials, a bouncing back, and then a steep decline in 2021 and 2022 (see Figure 2). In early 2020, 78% said they would want to work, but that dipped to 70% in 2022. That’s another all-time low in the nearly 50-year history of the survey. (To be fair, the majority still say they would want to work).

Figure 2: Percent of U.S. 12th graders who say they would want to work even if they had enough money, 1976-2022. Source: Monitoring the Future

Another way to look at it: The number of 18-year-olds who said they would not want to work if they had enough money went from 22% in early 2020 to 29% in 2022, a 32% increase in two years. A lot more young people are seemingly not intrinsically motivated to work.

Other indicators show the pattern as well. Expecting work “to be a very central part of my life” slid from Boomers to Millennials and then ticked up after about 2005 – until it, too, crashed after the pandemic (see Figure 1, previously). While 27% said they expected work to be a central part of life in early 2020, only 19% agreed in 2021 and 2022. That’s a decrease of 30%, and another all-time low since the survey began in 1976. Apparently work is less central to teens since the pandemic (and/or they heavily favor work/life balance – and which language you use might depend on which side of the desk you’re on).

Not only are 18-year-olds less focused on work, they are less likely to expect they will enjoy it. In the 2000s, Millennial 12th graders were more likely than Boomers were in the 1970s to expect that their future chosen work would be extremely satisfying (see Figure 1, previously; the students are asked to indicate what work they expect to be doing when they are 30 years old, and then to indicate how satisfying they think they will find this work).

Then, as 18-year-olds transitioned from Millennials to Gen Z, fewer began to believe that their future work lives would be satisfying. Nearly 77% thought so in 2013. As late as 2019, it was 71%. But by 2022, only 59% thought their career would be extremely satisfying – a 23% drop and another all-time low.

Thus, high school seniors’ work ethic declined significantly between 2020 and 2022. That’s what they say themselves; this conclusion is not based on the complaints of managers, viral TikToks, or even a one-time poll. Instead, the decline is appearing in a nationally representative, anonymous survey of 18-year-olds conducted each year. Young people in 2021 and especially 2022 were less willing to work overtime, less likely to want to work if they had enough money, less likely to say work would be a central part of their lives, and less likely to expect that their future chosen work would be satisfying. Gen Z, by their own admission, has a work ethic problem.

Could work ethic have declined among all generations between 2020 and 2022? A recent paper argued that the long-term decline in work ethic since the 1970s is completely due to people of all ages being less focused on work (a time period effect), and not to a generational decline. However, that paper made some strange analytic choices, like assuming generational change is categorial (breaking sharply at the birth year cutoffs) when it’s actually almost always linear (building year by year). The paper also used a method (APC analysis) that is well documented to produce different results depending on its analytical assumptions.

More convincing: Gallup data show a decline in work engagement among U.S. adults as a whole since 2020. That decline was especially steep among employees under 35 years old.

Thus, the declines in work ethic are likely due to both generation and time period. Arguably, though, changes in younger employees’ work ethic has a bigger impact – they are the unknown quantity managers are trying to figure out, and may be the most susceptible to quitting. Either way, whether the decline is mostly among younger Gen Z’ers or among everyone, these are stunning declines in a short period of time.

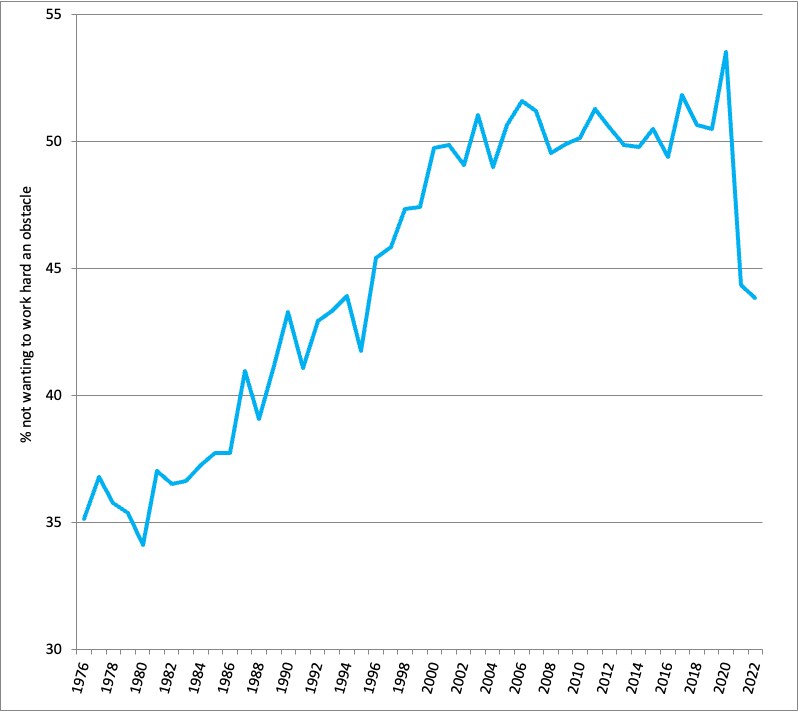

There’s another interesting trend in the survey data: Despite their self-admitted lower work ethic, 18-year-olds in 2021 and 2022 were actually less likely to believe that “not wanting to work hard” would be an obstacle to getting the job they wanted (see Figure 3). This is a big disconnect from previous years, when teens who said they didn’t want to work overtime also acknowledged that these attitudes might make it harder to get their chosen work. In early 2020, 54% thought not wanting to work hard might be an obstacle. By 2022, it was 44%, a 19% drop. So, by 2021 and 2022, 18-year-olds seem to be saying that they will be less focused on work, but that this won’t be a problem.

Figure 3: Percent of U.S. 12th graders who say that “not wanting to work hard” will be an obstacle to getting their chosen work, 1976-2022. Source: Monitoring the Future

So why did work ethic plummet in 2021 and 2022? There are a few possibilities. First, post-pandemic burnout might have played a role – after lockdowns, virtual school, and fights over masks, Americans were just plain tired. However, you could easily argue the opposite – by 2022, the pandemic was waning and these measures were mostly gone, which could have led to happiness and a “let’s get back to normal” attitude. Yet that didn’t happen.

Second, perhaps the decline in work centrality was due to a reset of priorities after the pandemic. We were reminded that life might stop in an instant – why spend so much time working? (As the old canard notes, “On their deathbed, no one ever said ‘I wish I spent more time at the office.’”)

Third, the job market was strong during 2021 and 2022. The “Great Resignation,” mostly of older workers, meant that younger prospective employees had more opportunities – and thus more power. In that environment, more could say they wanted to favor work-life balance, and employers had to listen.

Fourth, perhaps the popularity of a lessened work ethic spread on social media – for example, the viral TikTok videos on quiet quitting. However, those videos rose to prominence in the second half of 2022, after work ethic had already plunged among 18-year-olds. Thus, the attention around quiet quitting was likely a symptom, not a cause, of the decline in work ethic.

Fifth: The cause might lie in more subtle and indirect cultural changes. Gen Z is noticeably more pessimistic than Millennials were at the same age, including about capitalism. Their locus of control is also more external – they are more likely to believe that what they do doesn’t matter much. They seem less convinced they can become economically successful. They might be thinking, why work hard? It’s a rigged system anyway.

But these are just a few possibilities. I think it’s still a bit of a mystery why work ethic dropped so much in 2021 and 2022. I’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments – what happened to work ethic in the last few years?

To quote the late, great Buckminster Fuller, who said this back in 1970:

"We should do away with the absolutely specious notion that everybody has to earn a living. It is a fact today that one in ten thousand of us can make a technological breakthrough capable of supporting all the rest. The youth of today are absolutely right in recognizing this nonsense of earning a living. We keep inventing jobs because of this false idea that everybody has to be employed at some kind of drudgery because, according to Malthusian Darwinian theory he must justify his right to exist. So we have inspectors of inspectors and people making instruments for inspectors to inspect inspectors. The true business of people should be to go back to school and think about whatever it was they were thinking about before somebody came along and told them they had to earn a living."

Yet again, an excellent piece. First, I want you to know just how much I value your work and how frequently I use it in my own teachings, presentations, supervision, and counseling sessions. Thank you.

My opinion is that causality can also be ascribed to the sharp, yet not novel, rise in postmodern deconstructionism being taught across colleges and universities. Those students have younger siblings, and the graduates of those insitutions across the past 12-15 years (when it really exploded) have found jobs in K-12 education and corporate America, influencing yet more young minds.

When young people are taught that literally nothing is real, everything is merely a construct of a construct built by oneself (or others), and that well anchored ideas and beliefs are not merely uncommon but in some cases harmful or hateful, that leaves them disillusioned and unpassionate, verging on nihilism. They have no mooring from which to view the world, no stable sense of identity from which to form opinions. Their lens is constantly refracting based on what they think others expect of them, which itself is constantly changing.

Life has become a house of mirrors for this generation, and because they have no anchor point, they have no place from which to assert themselves, take a stand, and stop reflexively reacting to the latest stimulus. As such, this current generation has gone adrift in its own echo chamber of self-inflicted lethargy. And because it has been taught only to tear down and reject - never to build - any efforts to realign based on reason or truth are wholly rebuffed, thus perpetuating the feedback loop of disconnection and misery.

This is why your work, along with Jonathan Haidt, Zach Rausch, Lenore Skenazy, Bari Weiss, Jordan Peterson, and many others is so, so important. It offers a path out of this psychological dystopia. Keep it up please, we need you!