Is the adolescent mental health crisis real, or just an illusion?

What the New York Times got (spectacularly) wrong – and why the time for denial is over

The last few years have engendered a great deal of discussion about a mental health crisis among adolescents and young adults. Anxiety, depression, self-harm, and suicide have all increased in these age groups since 2010.

But what if that’s all an illusion, simply a product of changes in screening practices and medical records? Maybe there isn’t an adolescent mental health crisis after all. That’s the case made by David Wallace-Wells in a recent piece in the New York Times.

Is he right?

Wallace-Wells begins by pointing out that in 2011 there were “a new set of guidelines that recommended that teenage girls should be screened annually for depression by their primary care physicians and … required that insurance providers cover such screenings in full.”

This sounds damning: Perhaps more screening by doctors led to more documented cases of depression among teen girls after 2011. The problem: none of the evidence for the rise in teen depression in the U.S. — at least none I’ve used or documented — relies on doctor screenings. Instead, the data come from surveys conducted at schools and in homes. One of these studies, the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, is specifically designed to determine how many people suffer from depression and other conditions apart from any interaction with the medical system. Thus, changes in physician screenings and diagnoses are not relevant. It’s the first argument in the article, and it’s a complete red herring.

Wallace-Wells then notes that in October 2015 hospitals were newly mandated to “record whether an injury was self-inflicted or accidental.” One paper found that this change nearly doubled rates of self-harm in a database of insurance claims from 5 health care systems in 9 states.

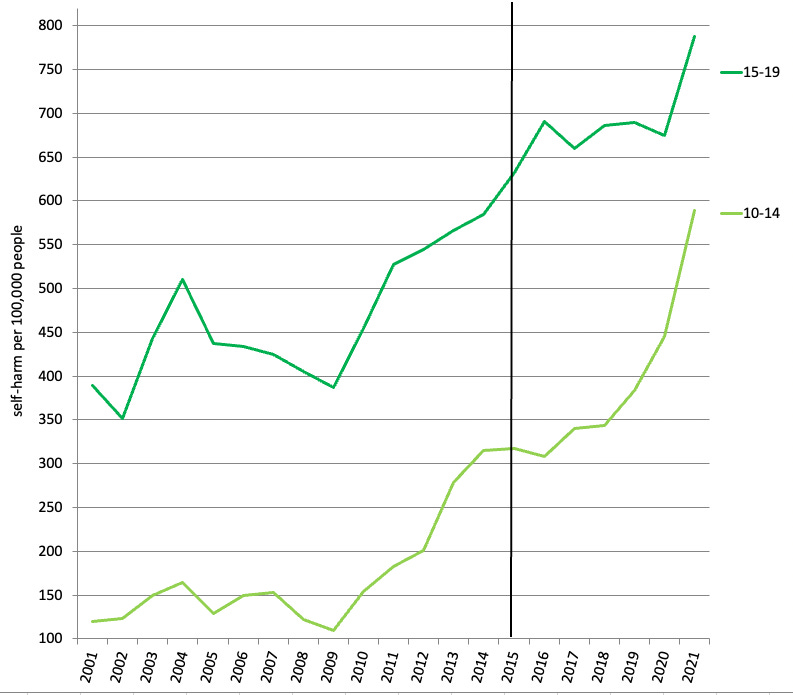

Again, this sounds damning: Perhaps the increase in self-harm behaviors among teen girls from 2010 to 2021 is just an artifact of a hospital coding change in 2015. If so, there should be a sudden change in rates of emergency room visits for self-harm between 2014 and 2016 and very little change in the years before or after.

But that’s not what happened. Instead, rates of self-harm among girls increased both before and after 2015 — the line in the figure (see Figure 1). In fact, self-harm rates actually declined slightly between 2014 and 2016 among 10- to 14-year-old girls — instead, rates of self-harm increase the most 2009-2014 and then again 2016-2021. That’s exactly the opposite of what you’d expect if a 2015 change were driving the trend.

Figure 1: Emergency room admissions for self-harm behaviors, U.S. girls and young women, by age group. Source: WISQARS database, CDC. Updates Figure 6.36 in Generations.

And, as Zach Rausch has shown, rates of hospitalizations for self-harm have also soared, suggesting the increases are not due to people being more willing to go to the emergency room; hospitalizations usually occur only in the most severe cases, and that is determined by doctors, not patients. Rausch also found that rates of self-harm hospitalizations have actually declined among older women since 2010; if the coding change had an effect, there should have been increases across all age groups. Instead, the rise appears only among 10- to 19-year-old girls and young women.

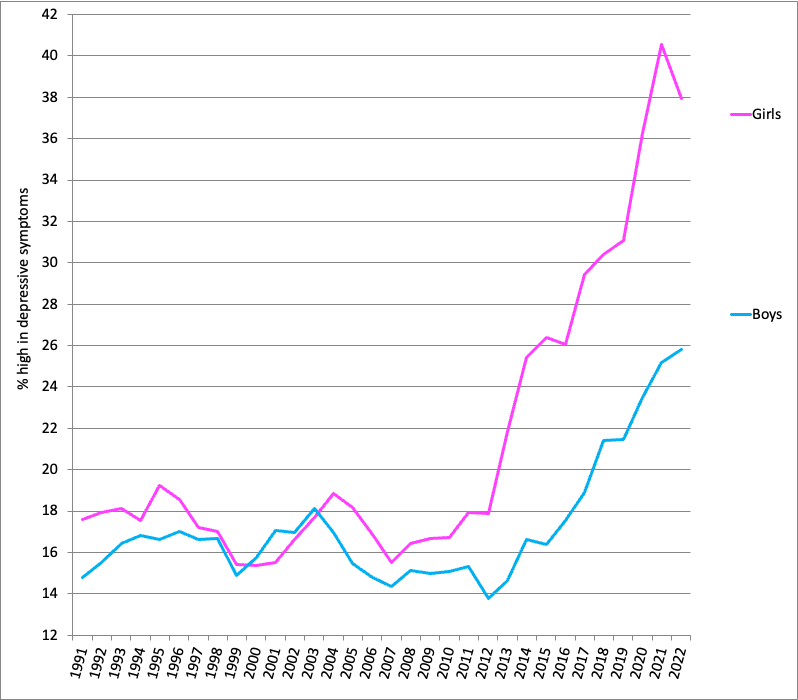

There’s another reason to doubt that the adolescent mental health crisis is due to medical coding changes or increased accessibility of medical care: Survey data, which is not subject to these confounds, shows exactly the same trend as behavioral data. One of the surveys that goes back the furthest is Monitoring the Future, which has asked 8th, 10th, and 12th graders questions measuring symptoms of depression since 1991, including whether they agree “Life often seems meaningless,” “I feel that I can’t do anything right,” and “I feel that my life is not very useful.” Because these items do not ask participants to self-diagnose as depressed or anxious, that helps rule out the possibility that any changes are due to shifting definitions of mental health terms.

Since 2012, American teens were much more likely to agree with these types of statements, with more than twice as many exhibiting high rates of depressive symptoms (see Figure 2). The increase is especially large among teen girls: while only 18% had high levels of depression in 2011, 40% did by 2021.

Figure 2: Percentage of U.S. 8th, 10th, and 12th graders high in depressive symptoms. Source: Monitoring the Future. NOTE: Graph shows percent with an average score of 3 or above (neutral to agreement) on six items measuring symptoms of depression on a 5-point scale. Updates Figure 4.6 in iGen.

Critics often dismiss self-report data by saying any trends could be caused by people being more willing to admit to problems, presumably due to a decrease in stigma around mental health issues. If that were true, one would expect a steady increase in self-reports of symptoms beginning many decades ago, especially in the 1990s when SSRI anti-depressant medications such as Prozac surged in popularity and mental health became more widely discussed. Instead, teens’ self-reports of symptoms actually decreased slightly between the early 1990s and the early 2010s and then suddenly increased (see the figure above). The context of this study also matters: Monitoring the Future is an anonymous survey that also asks about illegal drug use, so every precaution is taken to make sure the data are not identifiable, and that is communicated to participants. Plus, the trend in the self-report data is very similar to the trend in self-harm and suicide, neither of which involve self-report.

Wallace-Wells spends much of the rest of the piece on suicide data, which he calls “the most concrete measure of emotional distress” – a statement that’s a stretch, considering that suicide is influenced by so many different factors (including gun availability) and is, thankfully, a much more rare occurrence than depression or anxiety. He notes that “the American suicide epidemic is not confined to teenagers.” Although that’s true, it ignores two important things.

First, the suicide rate for middle-aged adults has changed little since 2010 while the rate for teens and young adults has soared (see Figure 3). As I showed in a previous post, the highest suicide rates in 2021 were among men in their 20s. The age gap in suicide has narrowed considerably, something Wallace-Wells does not discuss. Neither do critics who argue that suicide has increased more among the middle-aged; they often post suicide data comparing a year in the early 2000s with more recent data, conveniently sidestepping the lack of change in this age group in the last decade. When the suicide rates of the youngest adults in the prime of life starts to get close to the suicide rate of middle-aged adults, it’s time to pay attention.

Figure 3: Suicide rate by age groups, U.S. Source: WISQARS database, CDC

Second, rates of major depression — in a cross-section of the population, not in interactions with the medical system — have increased a huge amount among teens and young adults while staying stable or even declining among the middle-aged (see Figure 4). Something is clearly going wrong with the mental health of the young much more than among the middle-aged. These are not rare issues: One out of five U.S. adolescents experienced major depression in 2021-22, more than double in 2011.

Figure 4: Major depressive episode in the last year, U.S., by age group. Source: National Survey of Drug Use and Health

Wallace-Wells concludes, “There may be some concerning changes in the underlying incidence of certain mood disorders among American teenagers over the past couple of decades, but they are hard to separate from changing methods of measuring and addressing mental health and mental illness.” That statement is patently false. National studies have measured depression and depressive symptoms using exactly the same items over the years (thus there are no “changing methods of measuring … mental health”), the increase appears in screening studies of the whole population unconnected with the medical system “addressing mental health and mental illness,” and the increase in self-harm among teen girls shows no evidence of being caused by a coding change.

Science tells us to consider many different types of data and then come to a conclusion based on the preponderance of the evidence. No one type of data is perfect, but when nearly all types show essentially the same trend, that suggests something is happening. Neither coding changes nor access to medical care can explain why both self-report and behavioral data would all point toward a mental health crisis among one age group (teens and young adults) and not among another (the middle-aged).

Wallace-Wells suggests that we should not “find ourselves panicking over charts” because they show changes of “only” a few percentage points. If we shouldn’t panic when teen depression has doubled, teen and young adult suicide rates have soared, and self-harm among 10- to 14-year-old girls has quintupled, then when should we panic? When a third of teens experience major depression every year instead of “only” 20%? When even more 5th and 6th grade girls cut themselves and land in the emergency room?

There’s another way to look at this: Young people are telling us, with both their words and their actions, that they are suffering. Are we going to listen to them, or cover our ears and deny that there’s any problem?

Of course you’re correct, but may I make an argument why the New York Times might have unwittingly stumbled into being right, too?

This is the key:

“ Wallace-Wells begins by pointing out that in 2011 there were “a new set of guidelines that recommended that teenage girls should be screened annually for depression by their primary care physicians and … required that insurance providers cover such screenings in full.””

What if depression increased not, as Wallace-Wells argues, because screening found more of it… but because *screening itself causes depression*??

My case for that is here:

https://gaty.substack.com/p/how-we-make-children-miserable-and

In brief: doctors and teachers are “checking in” far far more than ever before on kids’ sad feelings, and just like the trans social contagion, you get what you measure.

So the times guy may be right, only not in the way he thinks…

Excellent (cogent, incisive) analysis, Jean . . . I've been hoping you or Jon/Zach would respond to that NYT essay. Keep on . . .