Is there really a generational difference in identifying as lesbian, gay, or bisexual?

And what about behavior?

In the early 2000s, same-sex marriage was a divisive culture war issue. By 2015, it was legal nationwide in the U.S. -- just one sign of the enormous shift in attitudes toward lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) individuals.

Along with these changes in attitudes, polls find that more young adults in the U.S. identify as LGB than older adults. That doesn’t necessarily mean anything has changed, though: That difference could easily be a function of age instead of generation. Perhaps young people explore different sexual orientations or identities more than older people, and that has always been true. To see if anything has really changed, we need data collected over several years so we can compare people of the same age at different times.

It would also be useful to have data over time on LGB sexual behavior. Some have argued that even if more young adults identify as LGB, that doesn’t mean more are having non-heterosexual sex. Maybe there is a difference in identity, but not in behavior.

In this post, I’ll tackle three topics, all with data up to 2022 that only recently became available:

1. How did attitudes toward LGB sexuality change since the 1990s in the U.S.? And how does that differ by political party?

2. Do more Americans identify as lesbian, gay, or bisexual now than in the past? (My colleagues and I just explored this question in a new paper.)

3. Do more American adults have sex with same-sex partners?

(Side note: If you’re accustomed to my writing about technology and mental health, you might wonder if you stumbled into the wrong Substack. You didn’t – I’m interested in any and all generational trends, and I will come back to writing about mental health in future posts).

Question 1: How much did attitudes toward LGB people really change?

Polls have shown a striking increase in support for same-sex marriage in the U.S. over the last 20 years. But how broad-based is this support? Does it extend to attitudes around LGB sexual behavior? And has it appeared across political parties?

The General Social Survey asks American adults their views about several different types of sexual activity. One is consenting adults having homosexual sex (a phrase I will use to avoid the confusing construction “sex with someone of the same sex”). The survey asks if this behavior is “always wrong,” “almost always wrong,’’ ‘‘wrong only sometimes,’’ and ‘‘not wrong at all.’’ At base, the question asks for a moral judgement of sexual behavior.

So how fast did these attitudes change?

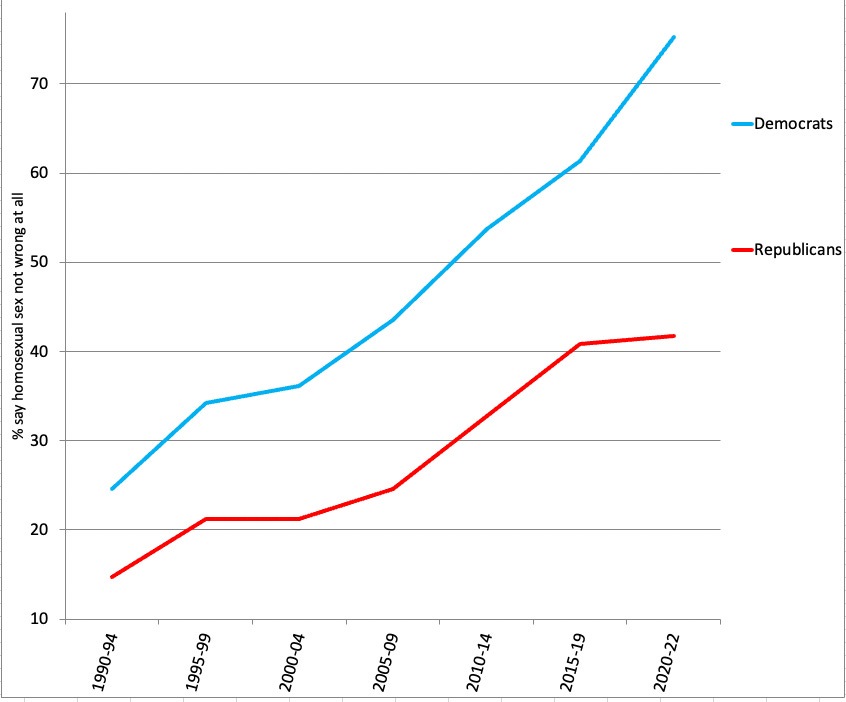

Extremely fast. In the early 1990s, only 1 out of 4 Democrats thought there was nothing wrong with homosexual sex. As late as the 2000s, the majority of Democrats thought there was at least sometimes something wrong with it. By the 2020s, nearly 3 out of 4 said it was not wrong at all. This is an enormous amount of change in a short period of time. Even among Republicans, the number believing homosexual sex was not morally wrong nearly quadrupled (see Figure 1). This is among U.S. adults of all ages; the numbers are even higher among young adults.

Figure 1: Percent of U.S. adults who say that homosexual sex between consenting adults is “not wrong at all,” by political party identification, 1990-2022. Source: General Social Survey. NOTE: Independents with no lean not shown.

Question 2: Do more people identify as LGB, and does that differ by generation?

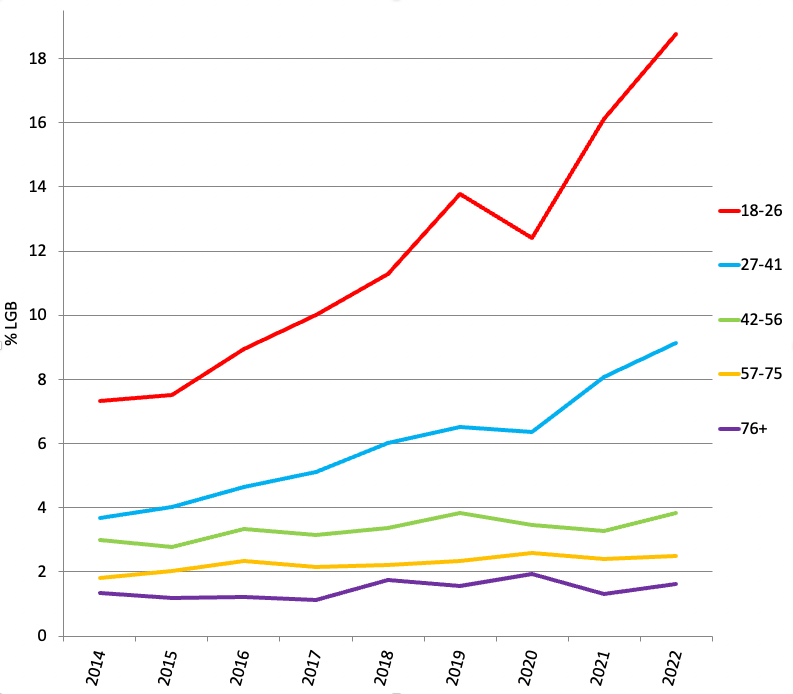

The CDC’s Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey has asked U.S. adults about their sexual orientation since 2014. Since then, the number of young adults identifying as LGB has more than doubled -- in just 8 years (see Figure 2). By 2022, nearly one out of five young adults considered themselves something other than straight.

Figure 2: Percent of U.S. adults identifying as lesbian, gay, or bisexual, by age group, 2014-2022. Source: Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey, CDC. NOTE: Similar to Figure 6.9 in Generations, but updated to 2022. Age groupings are based on the age of adult Gen Z, Millennials, Gen X, Boomers, and Silents in 2021. Our recent academic journal article uses different age groupings and finds similar trends.

LGB identity also doubled in the next older age group, 27- to 41-year-olds, who were all Millennials by 2021. There was little change among those 42 and older.

This data suggests there has been a generational shift. Thus, the larger percentage of LGB Americans among younger adults (vs. older ones) in one-time polls is not just due to age differences. As 18- to 26-year-olds shifted from being Millennials (born 1980-1994) to being Gen Z (born 1995-2012) from 2014 to 2022, more identified as LGB. And as 27- to 41-year-olds went from a mix of Gen X’ers and Millennials to all Millennials, LGB identification grew. With little change in older groups, though, it wasn’t a time period effect (a change affecting all generations equally). It seems to be a generational effect with the largest changes among Gen Z, moderate changes among Millennials, and very little among Gen X, Boomers, and Silents.

Breaking the data down by specific sexual orientation (lesbian, gay, or bisexual) shows that much of the change is due to young women increasingly identifying as bisexual. More than 1 in 5 young adult women in 2022 identified as bisexual, three times as in 2014, just 8 years before. About 1 in 12 young men identified as bisexual. There are smaller, though still significant, increases in identifying as lesbian or gay among young adults.

Figure 3: Percent of U.S. 18- to 26-year-olds identifying as bisexual, lesbian, or gay, by gender, 2014-2022. Source: Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey, CDC. NOTE: Similar to Figure 6.10 in Generations, but updated to 2022.

Question 3: Do more American adults have sex with same-sex partners?

Some reports have suggested that increases appear primarily in LGB identification, but not much in behavior. In other words, more young adults identify as LGB, but they are not necessarily acting on it.

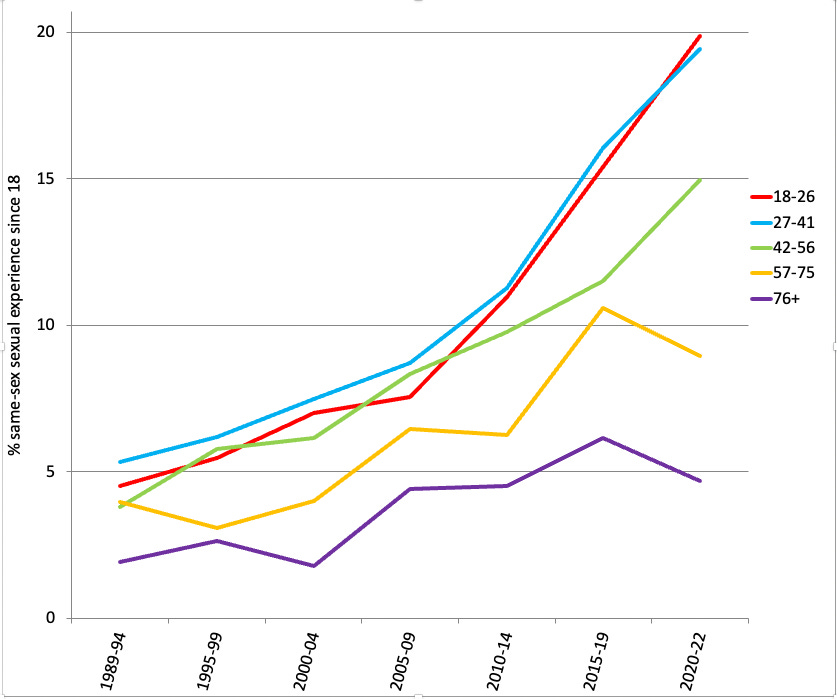

At least in the data from the General Social Survey, that does not appear to be true: There has also been a significant increase in young adults having homosexual sex (men with men and women with women). In fact, slightly more American young adults have had sex with a same-sex partner — 20% (see Figure 4) than identify as gay, lesbian, or bisexual — 18.5% (see Figure 2). The increases are even larger for 27- to 41-year-olds (the next older age group), perhaps because they have had more time to accumulate sexual partners since age 18.

Figure 4: Percent of U.S. adults who have had sex with someone of the same sex since turning 18, by age group, 1989-2022. Source: General Social Survey. NOTE: For more on the young adult trends, see Fig 6.14 and the surrounding text in Generations.

Although these estimates may not be exact, they definitely argue against the idea that young adults are identifying as LGB but not acting on it – for example, that young adults think it’s “trendy” to say they are LGB, but don’t actually have homosexual sex. Instead, the behavioral data is consistent with the changes in identity.

One small discrepancy: Older cohorts’ reports of homosexual sex have also increased since 2014, even though LGB identity hasn’t changed much in this group. Perhaps older cohorts have become more willing to admit to having homosexual sex even when they consider themselves to be heterosexual.

Overall, the data from national surveys shows consistent change: More Americans do not see anything wrong with homosexual sex, more younger adults identify as LGB, and more adults say they have had homosexual sex. If identifying as LGB was something young adults did just to be on-trend, we wouldn’t expect behavior to change as well. It could be argued they are having homosexual sex to be on-trend, but that’s a bit of a stretch.

It seems more likely that as acceptance of LGB identities and homosexual sex has grown in the U.S., so have these identifications and behaviors – particularly among younger adults, who may have more opportunity to explore their identities and their sexual behaviors.

That begs the question: Why did acceptance change so much? It is likely rooted in the increase in individualism, a cultural system that focuses more on the self and less on social rules. In Generations, I theorize that individualism grows as technology allows more independence (for example, labor-saving devices make living alone easier) and creates mass communication (making diverse identities more visible). Individualism says we should treat everyone as an equal and accept difference; there’s no need for people to be all the same and follow the same rules. Individualism is at the core of modern beliefs in equality, whether that’s centered on race/ethnicity, gender, or sexual orientation. With cultures growing steadily more individualistic, LGB identities are more accepted, and more people embrace them.

What other cultural trends might have caused the increase in LGB identities and behavior? I look forward to hearing from you in the comments.

I’m a psychologist who works with many college-age students. I have found that many identify as non-binary and might not respond to casting themselves as gay, lesbian, or bisexual. I was firmly corrected when I once used the term bisexual instead of non-binary. In my very tiny sample I have found in particular that women identifying as non-binary have often had only heterosexual encounters, or no sexual encounters. I would be interested in seeing research on non-binary identification and if it differs from your current findings.