It's not just you: Americans are still not hanging out

That's especially true for teens and young adults. Can parents help?

In the deep, dark early days of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, all many of us wanted was to see each other in person again. If only we had vaccines. If only it was safe.

A year later, we had those vaccines, and by 2023 the worst of the pandemic was squarely in the rear-view mirror: Schools were back in-person full-time, conferences had returned, face masks were rarely seen any more in the U.S., and the COVID death rate finally fell for good. By 2024, most of us thought about social distancing only when we spotted the occasional “stay 6 feet apart” sign someone hadn’t yet gotten around to removing.

Finally, we could get back to socializing with each other in person. But did we?

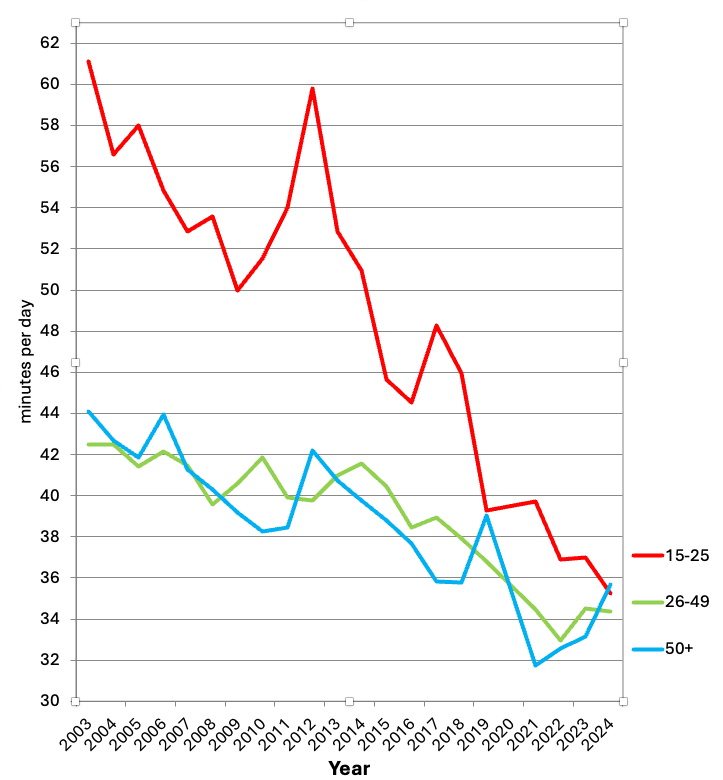

The Bureau of Labor Statistics recently released the 2024 data from the American Time Use Survey, which – as the name suggests -- has tracked how U.S. residents use their time since 2003. That data shows that socializing with other people in person was on a decades-long decline even before the pandemic, especially among young people (ages 15 to 25), where it plummeted from 61 minutes a day in 2003 to 39 minutes a day in 2019. As Derek Thompson put it, Americans – particularly the young -- stopped hanging out.

Then came the pandemic. The survey wasn’t fielded in 2020, but we can compare 2019 (before COVID) to 2021, a time of high case numbers when many events were still cancelled. Not surprisingly, in-person socializing dropped between 2019 and 2021, though by only 4 minutes a day – not as much as you might think.

More surprising: Our social lives never fully came back. The average American spent 38 minutes a day socializing in 2019 and 35 minutes in 2024 (see figure). Four years after the first COVID cases hit the U.S., our social muscles were still not at full strength. As a friend of mine put it, “We stopped having friends over during the pandemic – and then it was like we forgot how to do it.”

Minutes per day spent socializing in person, U.S. residents, by age group, 2003-2024. Source: American Time Use Survey, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

There are clear differences by age group. Adults ages 50 and older (the blue line) cut their social time the most during the pandemic. They then bounced back, though even by 2024 they were still lagging 3 minutes a day behind their 2019 levels. Adults 26 to 49 also cut back and then rebounded, though not by as much. Overall, adults 26 and older are on their way to digging out of the abyss of pandemic-era low social time; they seem to be slowly remembering how to get back to their pre-pandemic level of get-togethers.

Teens and young adults are a different story. Their social time (the red line) didn’t change during the pandemic, but then it actually declined even as the world opened back up in 2023 and 2024. In 2024, for the first time, adults 50 and older spent (very slightly) more time socializing in person than teens and young adults.

Young people’s social time is at an all-time low in the 21-year history of the survey. Fifteen- to 25-year-olds spend 26 fewer minutes a day socializing in person than they did in 2003. That’s three hours a week, 13 hours a month, and 158 hours a year less getting together with friends, having a face-to-face conversation, meeting for dinner, or chatting before seeing a movie together. No wonder so many more teens now describe themselves as lonely.

Why the continuous slide in social time for teens and young adults, even post-pandemic? The most obvious explanation is the increasing popularity of smartphones and social media. According to Gallup, U.S. teens spent an average of 4.8 hours a day using social media by 2023. That time has to come from somewhere, and it’s in part coming from in-person socializing. We know from other survey data that teens aren’t spending as much time going to parties, going out with their friends, riding around in cars, going shopping, or just hanging out than teens in the past.

When I talk to teens about this, many are frustrated. They want to get together with friends in person, but their friends don’t want to. I heard this from teens at the same school and in the same grade so many times that I finally realized they weren’t talking to each other about it. Each assumed the other didn’t want to get together in person, so they didn’t. It was just easier to be at home alone on their phones. Easier, but much more lonely.

Parents can help. Encourage teens to have their friends over. Allow sleepovers. Start early by joining the free-range parenting movement, giving kids and teens the freedom to roam their neighborhoods and hang out with their friends in person (this is Rule #8 in my new book, 10 Rules for Raising Kids in a High-Tech World). In my house, teens get their first smartphone when they get their driver’s license (Rule #5). Then there’s not the choice of Snapchat versus begging mom or dad for a ride – by the time they have access to social media on their phone, they can instead drive to a friend’s themselves.

Getting back to 2003 levels of in-person socializing may not be in the cards, especially for young people. But that doesn’t mean we should give up. Even a little more time face-to-face, in the same room, letting the conversation go where it will, hanging out within arm’s reach, human interaction with all its messy contours, will do us – and our kids – a lot of good.

Many in the media simply name the "pandemic" as the thing that hurt kids learning, ability to go outside, or socialize. But I think, as this article describes, it's important to consider the "how" in which COVID changed young people's behavior. It's led to increased screen time which we know impacts these elements of kids' well-being.

I would value knowing more details to this study, as it just isn't our experience with my 3 boys, now ages 17, 20, and 23, who live in Southern CA. Trying to figure out if they're more outliers. I definitely think having social parents is a big factor in encouraging social activity.