Millennials are in trouble – not economically, but mentally

Millennials are even dying at higher rates than Gen X’ers did at the same age

The youth of Millennials was one of exuberance. Born between 1980 and 1994, the oldest entered high school just as the economy started to pick up in the mid-1990s. Teen happiness, which had suffered during the Gen X era, rebounded. Optimism soared: more high school students expected to earn a graduate degree or work in a professional job, and more college students saw themselves as above average in their leadership ability, academic prowess, and their drive to achieve.

Then the Great Recession hit. It was a huge reality check for many Millennials used to the boom of the 1990s and 2000s. The economy improved after 2011, and so did the incomes and wealth of Millennials, but they – and the country – seemed to retain a bitter taste in the mouth.

During most of those years, though, Millennials did not show any notable changes in their mental health. Even when teen depression started to spike after 2011, Millennial young adults’ depression rates stayed about the same (in 2012, Millennials were ages 18 to 32; by 2021, they were ages 27 to 41).

Then things started to change for Millennials’ mental health – as my colleagues and I find in a new paper.

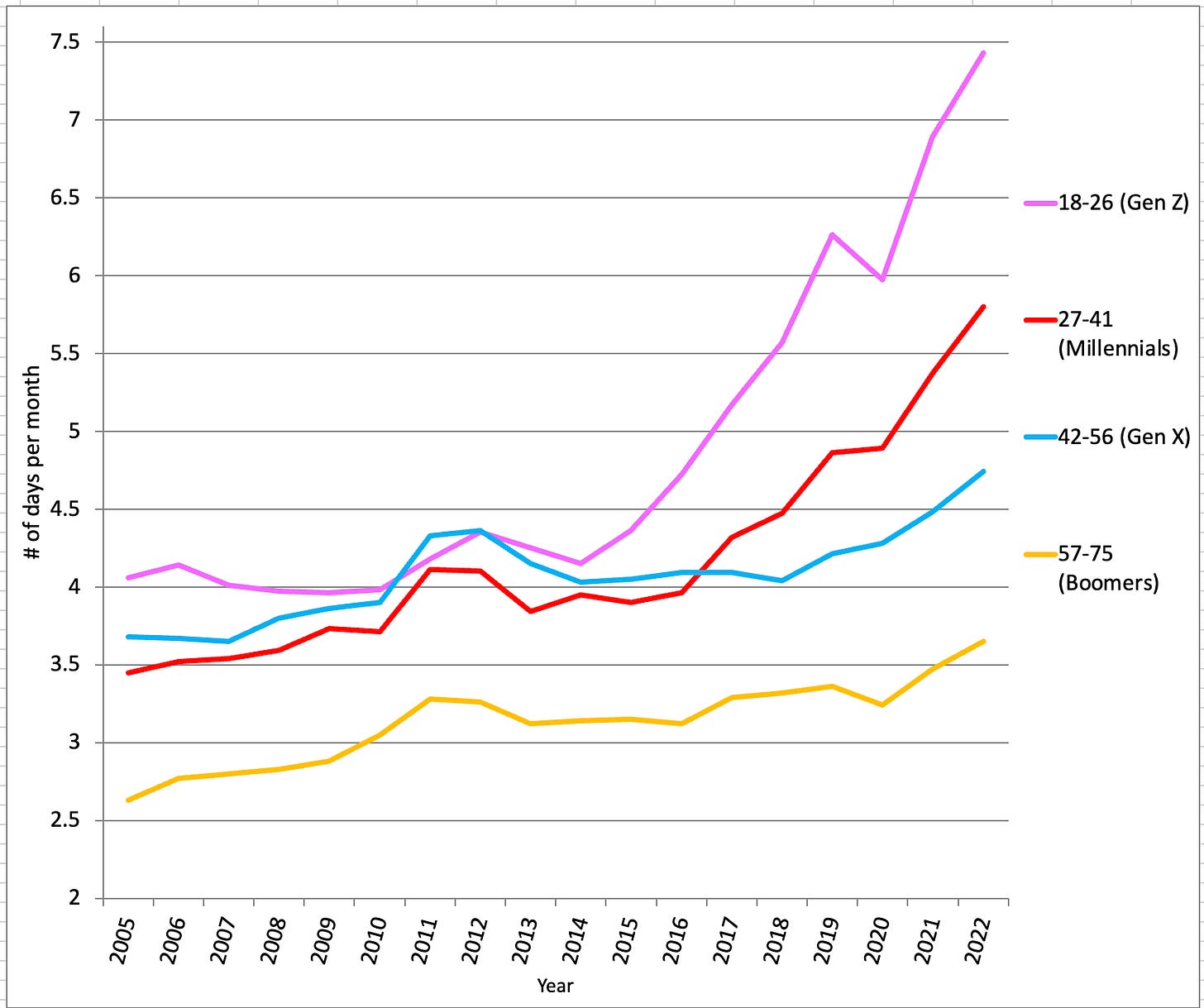

We looked first at days of poor mental health (feeling stressed or down), a one-item measure in the huge, nationally representative Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey of U.S. adults administered by the CDC. In this post, I’ve been able to update the graph to include the 2022 data, which wasn’t available when I was working on either the paper or on Generations.

As more young adults (ages 18 to 26) shifted from Millennials to Gen Z, days of poor mental health increased. That’s consistent with other research finding increases in mental health issues among young adults since 2014 or so.

What’s new is this:

Days of poor mental health also began to increase among 27- to 41-year-olds (whom I’ll call prime-age adults), especially after 2016. These are crucial years of adulthood, when many people marry, have children, and build careers. In just the 6 years between 2016 and 2022, this age group reported nearly two more days a month of poor mental health (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Number of days per month U.S. adults reported poor mental health, by age group, 2005-2022. Source: Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey, CDC. NOTE: Generational labels are based on the generation of the age group in 2021.

In 2005, when this data begins, prime-age adults were all Gen X’ers (born 1965-1979); by 2021, this age group was all Millennials (born 1980-1994).

The brand-new 2022 data are also noteworthy: In 2022, Millennials experienced about a half a day more of poor mental health on average than they did in 2021. So even as the country came out of the pandemic, with restaurants, concerts, and travel coming back, mental health issues continued to increase among Millennials.

What about more serious issues, like clinical-level depression? For that we turned to the National Survey of Drug Use and Health, a very large nationally representative survey that determines how many people in the population suffered from major depressive disorder in the last year, using clinical criteria.

We’ve known for awhile that clinical-level depression was increasing for teens after 2011 and for young adults 18 to 25 after 2014. When my colleagues and I first looked at this data in 2016, there wasn’t much if any change in depression rates among the next age group up (26- to 34-year-olds).

Then that changed. By 2021, 43% more 26- to 34-year-olds were clinically depressed than in 2016 (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Percent of U.S. adolescents and adults with clinical-level depression, by age group. Source: National Survey of Drug Use and Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. NOTE: Age is not reported in individual years after age 26 in this dataset, so age/generation groups are different than in Figure 1.

The increase is considerably smaller than for teens and young adults, but it’s of course not good news that adults in the prime of their lives are now more likely to be depressed. After a childhood and adolescence of happiness and positivity, depression has come for Millennials.

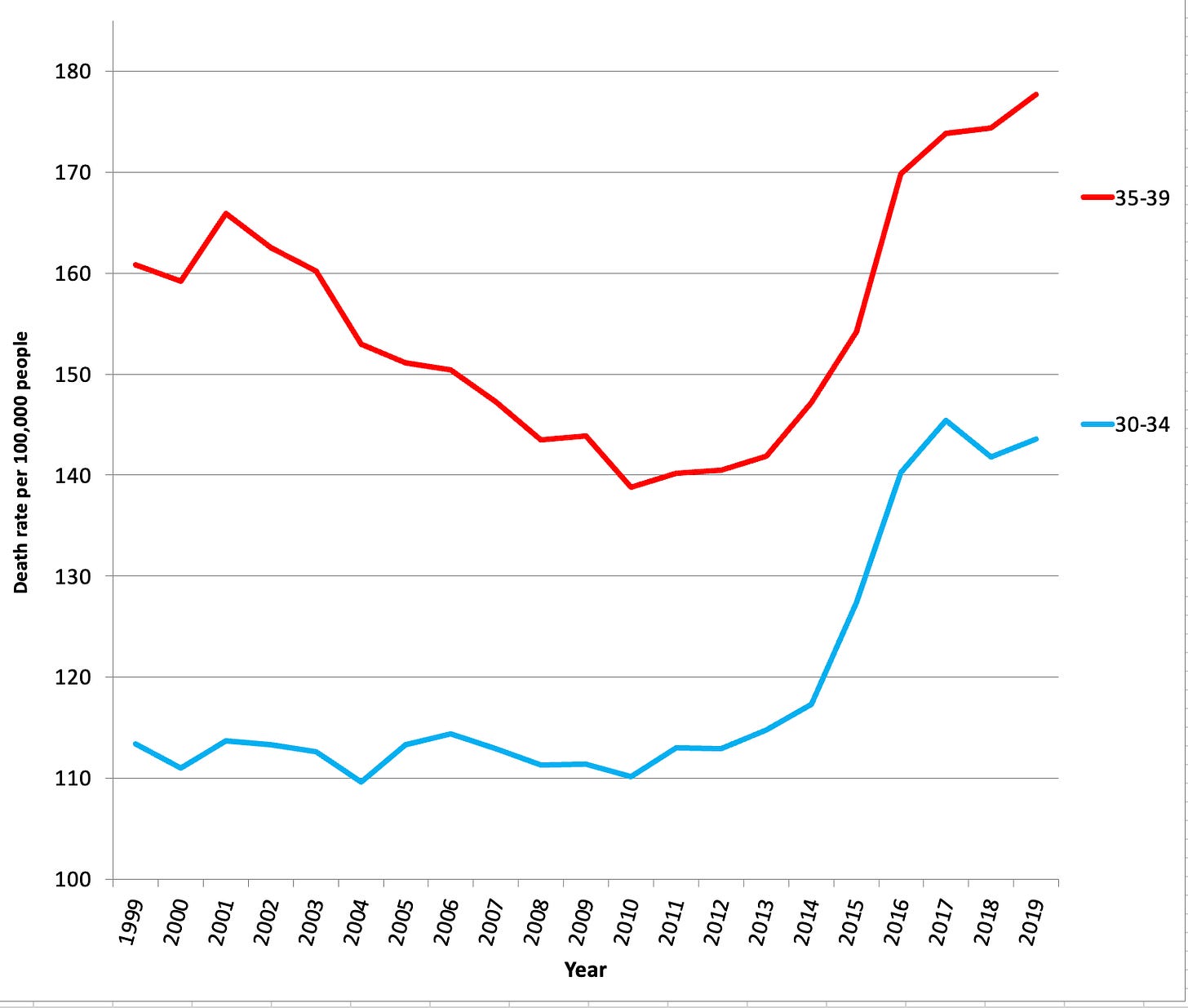

Sadly, it gets worse. In a well-known paper, Case and Deaton (2015) showed that death rates increased among middle-aged Boomers between 2000 and 2015. When working on Generations, I was startled to find that the trend now extends to younger adults: Death rates for adults in their 30s (all Millennials since 2018) were considerably higher in 2019 than they were 15 years before when this age group was all Gen X’ers. And this was before the COVID-19 pandemic hit in 2020 and brought up death rates — this analysis ends in 2019 (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Death rates among U.S. adults in their 30s, 1999-2019. Source: WISQARS, CDC. NOTE: Based on Figure 5.71 in the Millennial chapter of Generations.

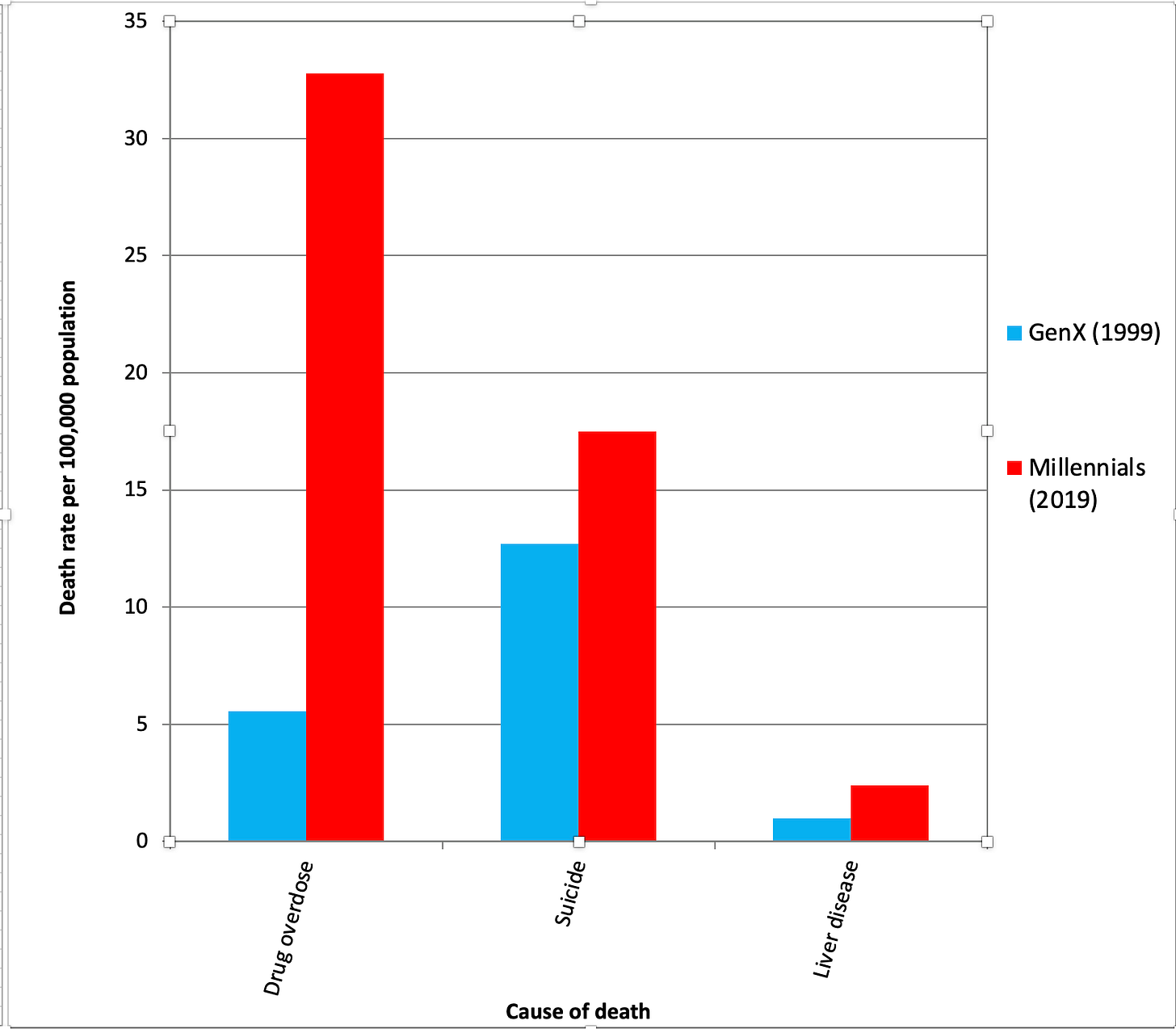

Just as with Case and Deaton’s findings, the biggest changes were in what they called deaths of despair: suicide, drug overdoses, and liver failure (which is often due to alcohol abuse). The biggest spike was in overdoses (see Figure 4), which in recent years are mostly opioids. Death rates from accidents, cancer, and heart disease were all going down over this time, but deaths of despair — those most linked to mental health — were increasing.

Figure 4: Death rates of U.S. 25- to 34-year-olds, by cause of death, 1999 (Gen X) versus 2019 (Millennials). Source: National Vital Statistics System, CDC. NOTE: Based on Figure 5.72 in the Millennial chapter of Generations

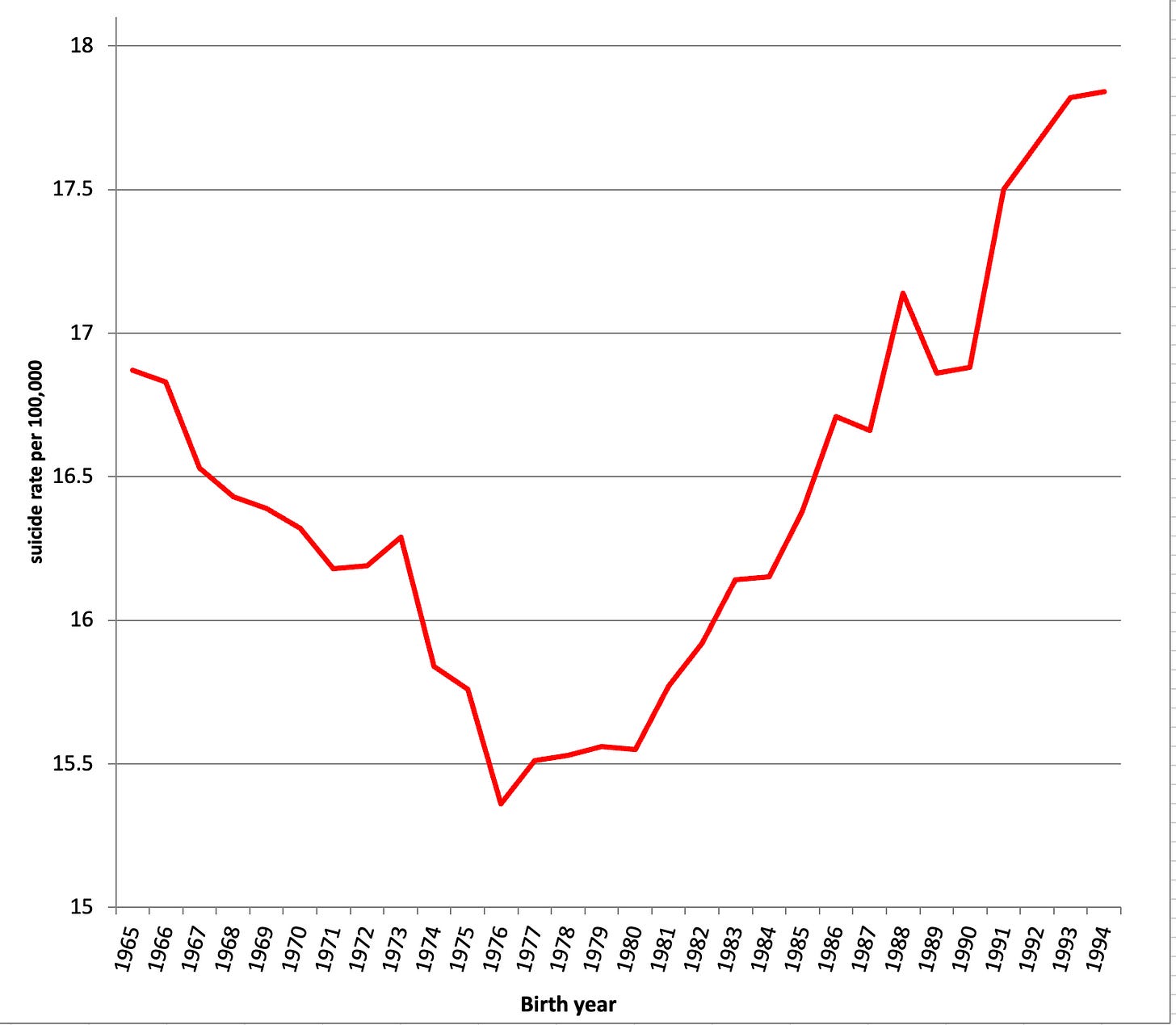

The changes in the suicide rate are especially striking. When I was working on Generations, I put the suicide rates for people of different ages during different years into a big datafile and had it output the suicide rate for each birth year controlled for age. That gives a view of suicide rates across generations apart from age differences.

That picture isn’t encouraging for Millennials: Suicide rates started to increase right as the birth years shifted from Gen X to Millennials (with 1980 as the first Millennial birth year), and continued to increase from there (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: Suicide rate of U.S. adults by birth year, 1965-1994, controlled for age. Source: WISQARS database, CDC. NOTE: Based on Figure 5.73 in the Millennial chapter of Generations.

To summarize: Premature death isn’t just a middle-aged Boomer issue anymore – and depression isn’t just a Gen Z teen issue anymore. Now these concerning trends have come for Millennials in the prime of their lives.

The question is: Why? One possibility is the same dynamic that’s played out for Gen Z teens: Less time spent with friends and family in person. Sure enough, young adults now spend less time with other people face-to-face than they did 10 or 20 years ago — and that decline began well before the pandemic (see Figure 5.79 in Generations). These decreases in social interaction aren’t as large as they are for teens, which is perhaps why the increases in depression also aren’t as large.

It seems unlikely the depression rise is linked to economic trends. Why would Millennials’ depression rates start to increase right as their median incomes increased? And it’s not homeownership – at least as of 2020, Millennial homeownership rates were barely different than those for Gen X and Boomers at the same age (see Figure 5.21 in Generations).

It’s also not Trump: The rise started before he was elected, and appears in both red and blue states (see Figure 5.74 in Generations).

The rise in depression among prime-age adults could have something to do with the pessimistic turn the country took in the 2010s. That’s when political polarization got worse and social media negativity ramped up. Millennials were right at the forefront of those trends.

I’d love to hear what you think: Why did depression increase among Millennials after 2016?

Another question: What can we do about it? That’s a lot harder to say. We might be able to stem the tide of depression among teens by putting more regulations on youth’s social media use, but that’s unlikely to fly for adults. Is it even possible to fix the toxic negativity of social media? Are there ways we can shift socializing back to more fulfilling modes?

Looking forward to hearing your thoughts.

A coupla ideas:

Not social media but the phone itself. The phone is the physical interruptor of social interaction, the "I have to take this" or the "let me take an hour to scroll for must-see pictures of my cat."

Secondly, as our senses (not just our brains) take in the effects of climate change, the great disconnect between the fires this time and what we preoccupy our politics with has got to have an effect. This might be called "There are no adults left" realization.

I'm almost 40 and I would say I frequently have bad mental health days. These are just my own experiences, but when I examine why I feel like things are wrong and I'm not doing very well, I reflect on the damage done from about the 1970s to today to a lot of institutions that I always felt like you were supposed to be able to rely on when you get older.

One issue is that we've shredded the notion of the kind of tight-knit communities that existed before the WWII suburban boom. Towns where you knew a lot of your neighbors, where you hung out on porches and talked to them, where you'd run into them when you were out in town, where your kids all went to school together, and you were involved in each other lives, even if just glancingly. I'm fortunate to live in a town that has a bit of a semblance of that, but it's also an expensive town to live in, because so much of the built environment after WWII was placeless suburban sprawl where barely anything like that is possible. And even in my town, people would often rather hide behind their Facebook profiles or lawn signs rather than engage with people in real life. I think we've just trained ourselves out of actual community, and that the atomization and isolation of our culture is just so intense right now. It can be really lonely to live in our culture today, so many economic and social forces go against the fabric of community.

Which leads me to another reason I get bummed out a lot of the time: the astonishingly anti-family position of many Americans, even in the supposedly family-friendly suburbs. My wife and I have a young kid, and I'm a big family guy myself, so I'm attuned to the hostility that kids and families often illicit from people. Cities can be tough for things like pushing strollers through, finding housing for families in, let alone safety and all. But even in the suburbs, I've seen so many meetings in rich towns where older people fight against market-rate housing because they fear children showing up who would go into schools and raise their school taxes. I mean how antisocial is that, to try to engineer a town without the vibrancy and hope of youth because you want lower taxes? And then that extends to other facets of life: fancy restaurants for fancy adults, fewer options for people with kids; the intolerance of people towards kids in public space, making totally normal kid sounds; the fact that you can't let your kids just be out in the world without people thinking you're a bad parent for not helicoptering over them 100% of the time. The list really goes on.

And finally, I think a lot of the thrust of liberalism in the 20th and 21st centuries has been bent toward encouraging, enabling, and basically insisting that people put themselves first and forget anyone else. So even in a marriage or long term relationship, people just look after their own interests without much thought to how it affects people they're involved with. Living with people is a big investment and can be super difficult, and requires emotional intelligence and a willingness to meet people where they are and sacrifice things for the sake of making something work. And our society is just so not set up for that. I see so many op-eds glorifying divorce, never having kids, just focusing entirely on yourself, as a couple of examples, and it edges the whole society to a self-centered almost nihilistic way of being.

When you're someone who wants to build a life with someone else, who wants to live in a tight community, who wants kids and wants the society to value kids, you just constantly run up against barriers to the kind of world that would make any of that really possible today. And when you think about how these were things we had by default for a really long time, before our society lost its mind in the 70s, it can feel super bleak.