Parent drug overdoses: The true cause of the adolescent mental health crisis?

Probably not. Here’s why.

Within a few days at the beginning of May, two papers published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) came to the same grim conclusion: More American children are losing their parents to drug overdoses.

The first, by Benjamin-Samuel Schluter and colleagues, estimated that 759,000 children in the U.S. lost a parent to a drug overdose between 1999 and 2020. The second, headed by Christopher Jones, estimated that 321,566 children lost a parent to a drug overdose between 2011 and 2021.

The findings made headlines, with experts noting the negative effects of parental death on children’s mental health – not surprisingly, losing a parent increases the likelihood of depression. Citing the new papers and other evidence, clinical data scientist Craig Sewall argued that “the crisis among parents that has unfolded over the past 2 decades is the #1 contributor” to the much-discussed adolescent mental health crisis.

This is not a new idea; others, including sociologist Mike Males, psychologist Andrew Przybylski, and psychologist Chris Ferguson have posited that the rise in teen depression is due to the struggles of their middle-aged parents with drug addiction and depression – and not, as I and others have argued, caused by the changes in teens’ lives wrought by smartphones and social media.

Could drug overdoses among parents be the primary cause of the teen mental health crisis?

In this piece, I’ll show why that is very unlikely, based on the number of children affected, trends in drug use among parents vs. non-parents, increases in depression and poor mental health within racial groups and regions, and mental health among middle-aged parents. Drug abuse and drug overdoses have soared among American adults, primarily due to the opioid crisis, and I do not deny that is an enormous public health issue. Here, I focus on whether those issues among adults can explain the rise in depression, self-harm, and suicide among teens that began around 2010-12.

Estimates or reality?

First, it’s important to know that the statistics on the number of children impacted by drug overdoses are estimates, not actual counts of children who lose a parent. Death certificate data do not include information on parental status, so researchers are forced to guess how many are parents based on demographic factors. Those estimates could be wildly off, especially if parents are less likely to die of drug overdoses than non-parents of the same age, race, and sex. In fact, one of the papers’ estimates is about 60% the size of the other for the 2020-21 period, suggesting a good amount of room for inaccuracy.

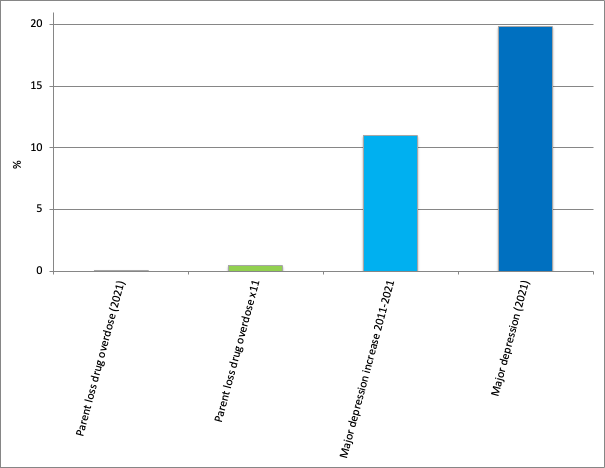

The Schluter paper estimated that about 100 children out of 100,000 lost a parent to a drug overdose in 2020. Using a different model, the Jones paper put the estimate at 63 children out of 100,000 in 2021. Both are less than .1% (1 out of 1,000) of children a year. Even if we assume that every child who loses a parent goes from not depressed to depressed and multiply the estimates over the 11 years of the increase in teen depression, the number of teens affected is still less than 1%. With teen depression rates rising from 8% in 2011 to 20% in 2021, the primary cause must be something impacting a much larger number of teens. The numbers aren’t even close (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Percent of children losing a parent to a drug overdose and percent of 12- to 17-year-olds with major depression, U.S. Sources: Jones et al. (2024) and the National Survey on Drug Use and Health.

But perhaps drug overdose deaths are just the tip of the iceberg of the dysfunction among middle-aged parents. For every parent who dies from a drug overdose there are many more who abuse drugs. And with the opioid epidemic surging, surely these numbers have gone up.

They have not – at least not among parents. The use of illicit drugs other than marijuana has barely budged among 35- to 49-year-old parents. It has, however, increased significantly among those without children at home (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Use of illicit drugs other than marijuana in the last 12 months, U.S. 35- to 49-year-olds, 2010-2022. Source: National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH). NOTE: NSDUH changed its measurement of drug use between the 2014 and 2015 surveys, so trends are reliable only before and after this breakpoint. Publicly available NSDUH data reports age only within groups, limiting the ability to examine custom age ranges. 35-49 is the age group most likely to have children at home and for those children to be older, including adolescents.

These diverging trends for parents versus non-parents may also explain why the estimate in the Schluter paper (100 children out of 100,000 losing a parent to a drug overdose) was so much higher than the estimate in the Jones paper (63 per 100,000). The Schluter paper seemed to assume that the rate of drug overdoses was the same among parents and non-parents of the same age, sex, and race/ethnicity. Except, as the NSDUH data shows, it is not. The estimate in the Jones paper was more informed; it used data from NSDUH to examine the number of drug users among those with children in the household. Even their estimate is likely too high, however, as it did not account for the increasingly large divide in drug use among non-parents vs. parents after 2019. With drug use rising only among non-parents, it seems unlikely parent drug use could account for the doubling in teen depression after 2012.

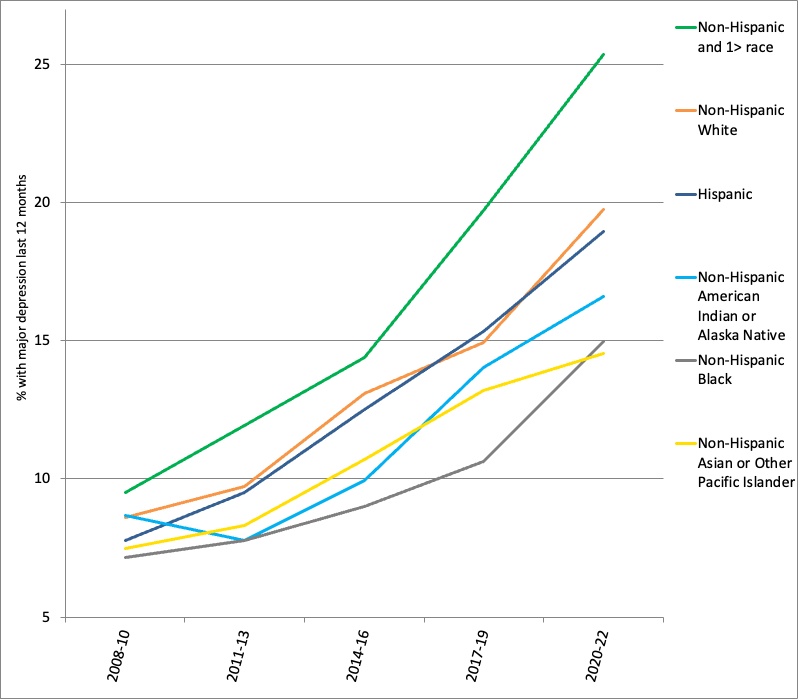

Plus, if parental drug overdoses were behind the rise in teen depression, we’d expect to see the same pattern by race and ethnicity for both – but we do not. The image below is the trend in the estimated number of children impacted by parental drug overdose by race and ethnicity in the Jones paper. That’s followed by Figure 3 showing the increase in teen depression by race and ethnicity using the same colors. The pattern is not the same. Increases in estimated parental drug overdoses were much higher among Native Americans, while the increase in depression among Native Americans teens was about the same as other racial groups’. Parental drug overdoses grew much more among Blacks than Asians, but increases in teen depression in those groups were similar.

Figure 3: Major depressive episode among 12- to 17-year-olds, by race and ethnicity. Source: National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Note: Years are combined to increase sample size within racial and ethnic groups.

Regional differences: Do they fit?

Perhaps opioid deaths and addictions, as well as other deaths of despair, have caused the adolescent mental health crisis via other routes – for example, through relatives and other adults in the community. If so, we’d expect the rise in mental health issues to be concentrated in the states with the largest per capita increases in deaths among the middle-aged. According to another study published in JAMA, those states are Indiana, Kentucky, Maine, New Hampshire, Ohio, Vermont, and West Virginia – not coincidentally, the states hit the hardest by the opioid epidemic.

Most surveys don’t report data state by state. One of the few that does, the CDC’s Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, asks U.S. adults about days when people feel “stress, depression, and problems with emotions.” Among young adults, poor mental health increased at the about same rate in states with smaller vs. larger increases in midlife mortality (see Figure 4). This suggests a cause other than rising deaths among the middle-aged.

Figure 4: Days of poor mental health among U.S. 18- to 25-year-olds, by states with higher vs. lower increases in deaths among the middle-aged. Source: Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. NOTE: BRFSS surveys adults 18 years old and over only. Higher mortality increase states are Indiana, Kentucky, Maine, New Hampshire, Ohio, Vermont, and West Virginia.

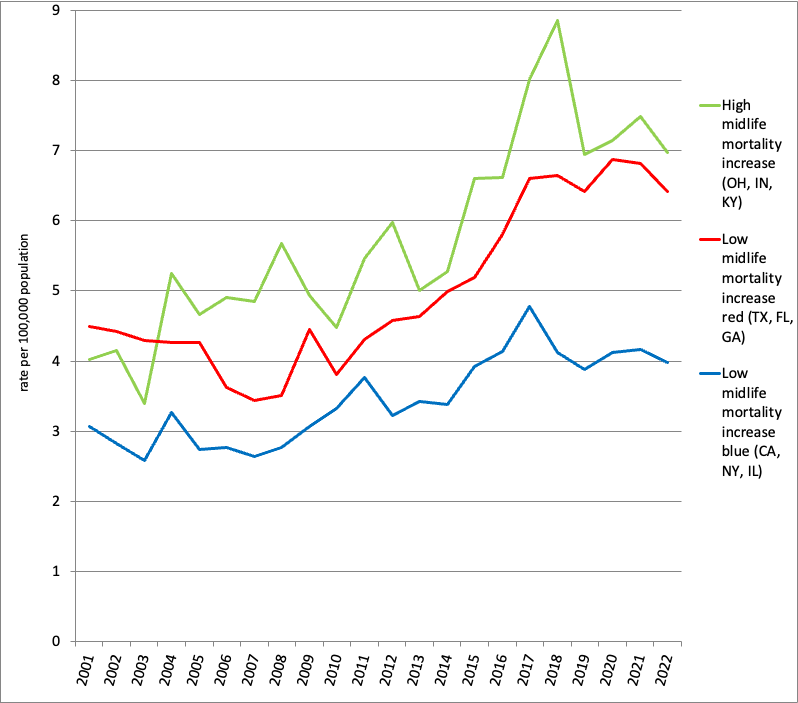

We can also examine teen suicide rates by state as long as their populations are large enough (when raw numbers are too low, the CDC does not report suicide data). For the states with the largest increases in midlife mortality, that’s Ohio, Kentucky, and Indiana. We can compare those to the highest-population states with low or no increases in midlife mortality: California, New York, and Illinois. However, we’re then comparing a group of three red (Republican-leaning) states with three blue (Democrat-leaning) states, and that may introduce confounds, especially with a statistic like suicide that might be influenced by state policies and regional cultures, such as access to guns or state funding for mental health interventions. Thus it might be wise to also include a group of red states with smaller or no increases in midlife mortality. The three with the highest populations are Texas, Florida, and Georgia.

The result: Adolescent suicide rates have increased across all three types of states. There is variation across regions, but most of that divide is around red vs. blue rather than low vs. high increases in midlife mortality. Since 2010, the suicide rate for 10- to 19-year-olds has increased 56% in states with high midlife mortality increases (all red), 69% in red states with low midlife mortality increases, and 20% in blue states with low adult mortality increases (see Figure 5). Thus, low vs. high midlife mortality rates do not seem to be the primary driver behind the increase in teen suicide. Instead, some other cultural or policy factor may have caused the larger increase in red states.

Figure 5: Suicide rates among 10- to 19-year-olds by groups of states. Source: WISQARS database, CDC. Note: Weighted by state population within each group.

Depression and poor mental health: Parents vs. non-parents

It’s also important to consider other pathologies among the middle-aged. Perhaps more parents are depressed, leading their children to be depressed. This is Chris Ferguson’s theory. “It’s intergenerational,” he wrote. “Kids are in pain because their families are in pain.” This is of course true for individual families; depressed parents may have depressed children, for a variety of reasons. But to explain the increase in teen depression since 2010, there would have to be a corresponding increase in depression among middle-aged parents.

But that, too, isn’t there. While teen depression has soared, depression among middle-aged parents has not changed (see Figure 6). And, similar to the rates of drug abuse, parents are actually less likely to be depressed than non-parents in the same age group.

Figure 6: Percent experiencing major depression in the last year, by age group and presence of children. Source: National Survey on Drug Use and Health.

What about more low-level stress? Here, we finally see some evidence of issues among middle-aged parents, but with two big caveats. First, the increase in stress among parents pales in comparison to the huge spike among young adults (see Figure 7). Second, the rise for parents began only during the pandemic years after 2019, making it an unlikely cause for the rise in teen depression that began in 2012. And, even with the pressures on parents during the pandemic period, they experienced fewer days of poor mental health than their peers without children at home.

Figure 7: Days of poor mental health in the last month, by age group and presence of children at home. Source: Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. NOTE: BRFSS data are by individual year of age, allowing a more comprehensive age range than NSDUH. Those 35 to 54 were the ages when adults were most likely to have 12- to 17-year-old children at home. BRFSS surveys adults 18 and over only.

(In his piece, Sewall wondered why I didn’t look at parents 34 and under. The answer is simple: They are unlikely to have adolescent children. Recent changes in drug use and depression among 26- to 34-year-old parents will be relevant for adolescent mental health after ~2030 when their young children become adolescents. For younger parent depression to have affected today’s adolescents when they were young children, there would need to have been a large increase in depression among 26- to 34-year-old parents in the late 2000s and early 2010s. There was not – depression rates in this group changed little during those years).

Conclusions

Overall, the picture of middle-aged parents in this data is quite positive: They are less likely to abuse drugs, less likely to be depressed, and less likely to be stressed than their childless peers. That might be because more stable and mentally healthy people become parents, or it might be because people become more stable and mentally healthy after they become parents.

These data also contribute to the age-old debate: Are parents happier, or less happy, than those without children? In the moment, parents often report less happiness. Parenting can be exhausting and not that much fun. But parents also report finding more meaning in life than non-parents. That might be why they are less likely to use drugs than their childless peers. Strikingly, parents are also less likely to be depressed. Having children at home may be protective against some of the downsides of middle age, such as loneliness, social isolation, and lack of purpose.

Given 1) the much smaller numbers of children who have lost parents compared to the large increase in depression, 2) the lack of any rise in drug use among parents, 3) that the pattern by race and ethnicity and by states differs for the rise in overdoses vs. the rise in teen depression, and 4) the lack of increase in depression among middle-aged parents, it seems extremely unlikely that drug overdoses, drug abuse, or depression among parents is the primary cause of the rise in teen depression since 2010. It’s also difficult to reconcile how an increase in adult overdoses in the U.S. could explain why young people in Europe, Latin America, or Australia – places that have not seen such a sharp increase in adult drug overdoses -- are also more likely to be lonely, depressed, and engage in self-harm than they were 12 years ago. It just doesn’t fit.

On the other hand, there is no denying that drug overdoses have soared among American adults. This is its own crisis – we don’t need to tie it to the increase in teen depression to pay attention to it.

I appreciate Dr. Twenge engaging this crucial issue, but her analysis suffers from omission of key data, orange-apples comparisons of survey and vital statistics, flawed geographical comparisons, and other serious problems. Essentially, she is arguing that 800,000 overdose deaths, 12 million overdose-related hospital emergencies, 10+ million drunken and drug offenses, etc. among ages 30-59 (the parents, parents’ partners, relatives, teachers, coaches, etc.) – all soaring during the 2010-2022 period, when teens' depression was rising – would not be a major cause of teenagers’ poor mental health. (In 2022, SAMHSA reported some 4 million drug-related ER treatments in the 26-64 age group in the US, a pattern of rising adult drug abuse occurring across the Western world.) I don’t want to bog down this comments section, but if interested in my response, see: https://mikemales.substack.com/p/how-jean-twenge-et-al-get-the-middle