Teens used to be happier. What changed?

Even post-COVID, few teens say they are “very happy”

One of the challenges of doing research on trends in mental health is finding survey data that goes back decades. The National Survey of Drug Use and Health, which measures clinical-level depression in a large sample, only has data back to the mid-2000s. Monitoring the Future (MtF) and the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS) both have data on depressive symptoms, but only back to 1991.

There are some ways around this, many of which I explored early in my career before these datasets were available. For example, I found that children’s and college students’ anxiety levels increased between the 1950s and the early 1990s by doing a cross-temporal meta-analysis (finding research articles that reported average scores on the same measure and seeing if those scores had changed over time). Other researchers also reported increases in depression rates among adolescents over this time.

Between the early 1990s and about 2010, though, teen mental health mostly improved — or at least didn’t get any worse. The teen suicide rate went down. In YRBSS, the number of teens saying they seriously thought about suicide declined between the 1990s and 2009 (this is Figure 5.68 in the Millennials chapter of Generations). In MtF, depressive symptoms went down slightly. So we have a clear picture of the decline or stability in teen depression from the early 1990s to 2010 and the huge rise after 2010-12, but there is no survey I know of that has tracked teen depression from the pre-1990s era to the present.

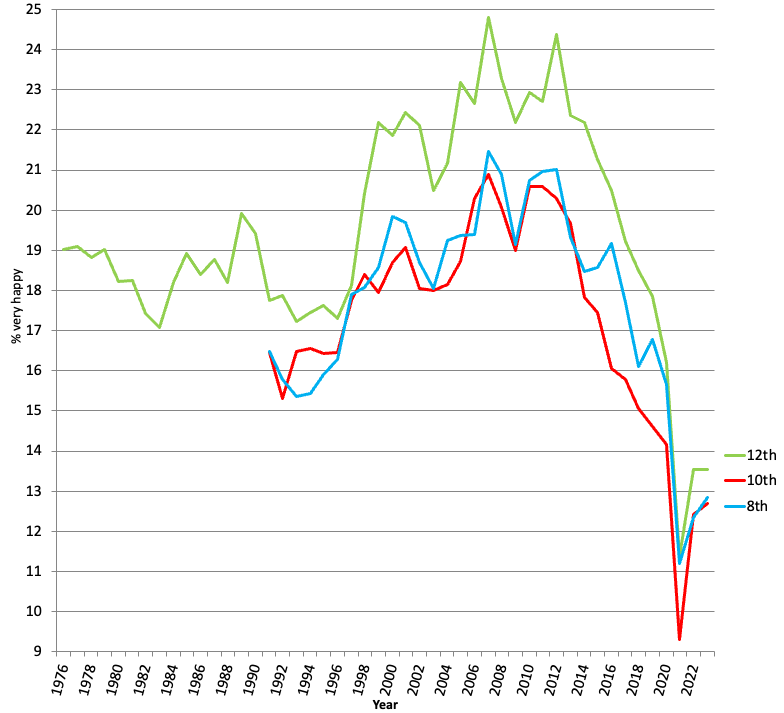

But we do have data going back further for one key indicator of psychological well-being: Happiness. Happiness has been measured in exactly the same way among high school seniors (17- and 18-year-olds) since 1976 in Monitoring the Future. The happiness item (“Taking all things together, how would you say things are these days – would you say you’re very happy, pretty happy, or not too happy these days?”) thus gives us the longest-running view of any indicator of psychological well-being among adolescents. (Happiness has also been measured this way among 8th and 10th graders since 1991.) So how has teen happiness changed over the course of six decades?

From the 1970s to the 1990s, high school seniors’ happiness had its ups and downs, declining during the recession years of the early 1980s, rebounding in the cheery mid- to late-1980s, and then falling again during the high-crime, high-unemployment early 1990s (see the green line in the figure). This was the era when young Gen X’ers wore black and listened to Nirvana and Pearl Jam.

Figure: Percent of U.S. teens saying they are “very happy,” 1976-2023. Source: Monitoring the Future. Analyzed by Jean M. Twenge for the Generation Tech Substack.

Then, by the late 1990s, the Windows ’95, early internet, booming 90s economy era took hold, and teen happiness came roaring back. By the time most teens were Millennials in the early 2000s (and presumably listening to Britney Spears and other peppy pop), teen happiness was at all-time highs. By 2007, 24.8% of high school seniors said they were “very happy,” the highest ever recorded (before or since). Happiness stayed fairly high even through the years of the Great Recession (2007-09) and was at 24.4% as recently as 2012.

That, as it turned out, was the end of an era. As smartphones and social media became pervasive in the 2010s, teen happiness plummeted.

These data show how unprecedented the happiness decline of the 2010s is. They are a strong counter against arguments I’ve heard from critics. For example, some claim that the decline in teen well-being has been ongoing steadily since the 1950s, and thus it can’t be due to smartphones or social media. This data clearly shows that’s not true. Teens were happier than previous generations in the 2000s, right before smartphones and social media became ubiquitous, and then, rather suddenly, they weren’t.

Others say that changes in well-being could be due to reduced stigma around mental health issues or other changes in how people self-report. If so, self-report changes would need to follow the same up and down pattern seen here. It seems unlikely that stigma against reporting (say) unhappiness increased during the 1990s and 2000s and then suddenly decreased during the 2010s. Changes in stigma are also seem like an unlikely explanation for trends in reporting being “very happy.”

There’s a sad coda to this story. Teen happiness fell precipitously during the COVID years – only 11.4% of high school seniors described themselves as “very happy” in 2021. Coming out of the pandemic in 2023, that increased to 12.7%. But that is still much, much lower than the 17.9% of high school seniors who said they were “very happy” in 2019. Teen happiness has still not bounced back from the COVID years even as the world opened back up.

In 2023 – the latest data available – the number of 8th, 10th, and 12th graders who were “very happy” was a little more than half of what it was in the early 2010s.

That has to change. Teens, talk to your friends about getting together in person instead of on social media. Spend some time away from your phone (and let your friends know you’re taking a phone break … or do it together!) My upcoming book 10 Rules for Raising Kids in a High Tech World discusses what parents can do: For example, delay giving your kids smartphones as long as possible, keep them off social media until 16 or later, and preserve sleep by getting devices out of your kids’ (and your!) bedrooms after lights-out. Policy makers, keep trying to get age verification on social media so 11-year-olds aren’t getting addicted to Instagram and TikTok.

The constant pressure of social media isn’t “just how kids are now.” It’s a trap of unhappiness.

When mid school and high school girls are at my overnight summer camps, they run around playing like little kids and seem very happy. There are no electronics at our camps, and they connect more deeply with peers than in their regular life. One of the main things they are lacking is community, and safe spaces where they can feel free to be authentic and share their stories.

Jean, hello, may we run this fascinating piece in the US Spectator? I’m mary@spectator.co.uk