The pandemic was bad for teen mental health. The smartphone and social media were worse.

By this point, most people are aware that there’s a crisis in teen mental health. It’s often assumed that the crisis is due to young people’s experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic – or at least that the pandemic made these trends significantly worse.

Did it — and if so, how much? And is it better now? Recently released data can finally show us trends in teen depression through the post-pandemic years. We can compare the impact of the smartphone and social media era of the 2010s to the impact of the pandemic, and also see how things resolved once the pandemic waned in 2022 and 2023. This post is in conjunction with the release of the paperback edition of Generations, which features lots of updated data and graphs — especially about Gen Z.

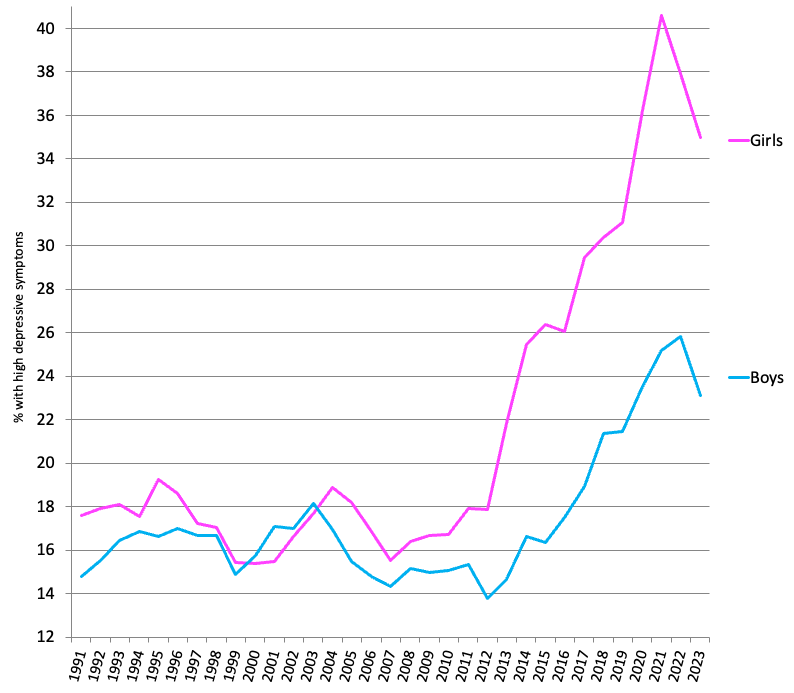

Figure 1 shows the percentage of adolescent girls and boys high in depressive symptoms from 1991 to 2023. We’ll consider both relative change (the percentage increase or decrease in how many more teens are depressed – for example, from 10% to 15% is a 50% increase) as well as absolute change (in percentage points – from 10% to 15% is 5 percentage points). Let’s take the trends chronologically.

Figure 1: Percent of U.S. 13- to 18-year-olds high in depressive symptoms, by sex, 1991-2023. Source: Monitoring the Future 8th, 10th, and 12th grade surveys. Notes: Shows those who score 3 or higher on the average of 6 items on a 1 to 5 scale. The 2020 data were collected in February and early March before pandemic shutdowns.

Though there are a few ups and downs, teen depression changed little between 1991 and 2012.

From 2012 to 2019 (the last pre-pandemic year), the number of depressed girls increased by 74% and 13 percentage points. From 2019 to 2021 (pre-pandemic to pandemic), it increased 31% and 9 percentage points. From 2021 to 2023 (pandemic to post-pandemic), it decreased 14% and 6 percentage points.

From 2012 to 2019, the number of depressed boys increased by 56% and 8 percentage points. From 2019 to 2021, it increased 17% and 4 percentage points. From 2021 to 2023, it decreased 8% and 2 percentage points.

Thus far, we can conclude:

1. The increases in depression from 2012 to 2019 – the years when smartphones and social media went from optional to nearly mandatory for teens – are much larger than the increases in depression from before to during the pandemic.

2. There were sharp increases in depression from before to during the pandemic (2019 to 2021), but these increases had already receded significantly by 2023, just two years later.

3. All of the changes are larger for girls than for boys, suggesting that environmental factors had a bigger impact on girls’ depression than boys’.

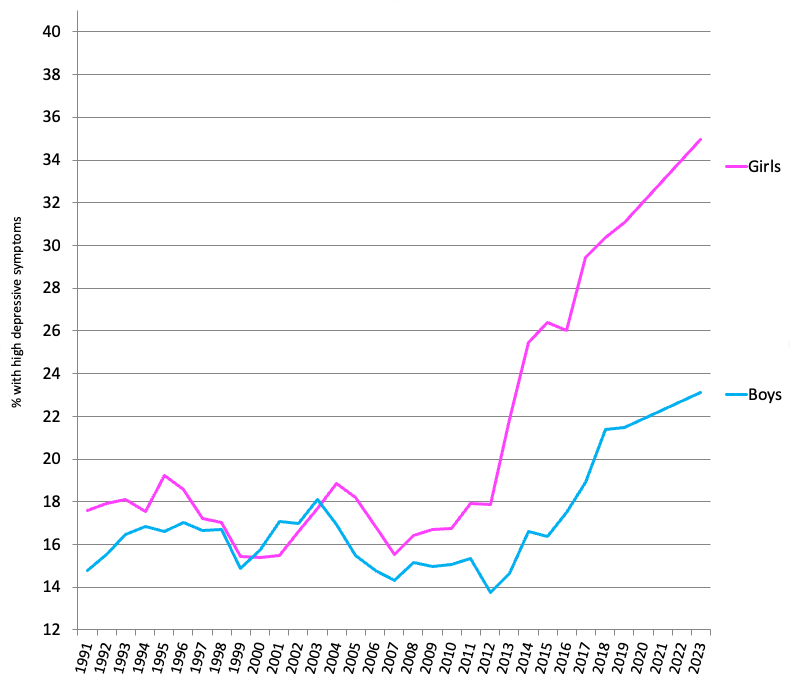

Another way to view the trends is to leave out the years most directly impacted by the pandemic (2020, 2021, and 2022) and connect the lines from 2019 to 2023 (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Percent of U.S. 13- to 18-year-olds high in depressive symptoms, by sex, 1991-2023, with 2020, 2021, and 2022 redacted. Source: Monitoring the Future 8th, 10th, and 12th grade surveys. Notes: Shows those who score 3 or higher on the average of 6 items on a 1 to 5 scale.

This shows a continued rise in teen depression from 2019 to 2023, but at a slower pace than the rise from 2012 to 2019. Still, the number of depressed girls rose 13% and 4 percentage points from 2019 to 2023, and the number of depressed boys rose 8% and 2 percentage points. So, even with post-pandemic declines, more teens were depressed in 2023 than in 2019 before the pandemic. That could be caused by lingering effects from the pandemic, and/or it could be caused by the continued increase in social media time and the popularity of those apps (for example, the huge growth in TikTok since 2020).

The overall conclusion: Even as the worst effects of the pandemic have waned, teen depression is still at historically very high levels. The shift toward a screen-based social life and away from an in-person social life was underway for teens a good eight years before COVID, and it’s continuing to make many teens miserable.

These trends also align with the introduction of the 1:1 initiative in 2012 and the decline in student tests scores that are continuing to drop today. Around 2012, schools began to transition to a more screen based education and the push for more edtech use in schools took off along with the profits of big tech. As an educator that focuses on supporting social skill development, students today are lacking the opportunity to develop their interpersonal skills, critical thinking skills and social self regulation. Add social media to the mix and the results are not good. We need to take a much more critical lens to all the edtech in schools and significantly reduce the amount of screen time during the school day while getting back to the basics with books, paper and pencils. The harms of social media go hand in hand with the overuse of edtech in schools.

No, the pandemic and especially the lockdowns and school closures clearly were FAR worse than smartphones and social media. It beggars belief that this is even a debate at all.