What the Lancet doesn’t want you to know about girls and self-harm

Suggesting a link to social media is apparently too controversial

In late June, an editor at the Lancet asked me to write a comment in response to the journal’s upcoming report on self-harm. In academic journals, comments usually react to another article or reflect on a social issue – they are the academic equivalent of an op-ed. Invitations to write a comment are usually sent to academics who have a particular focus, so editors can anticipate what they might write. Consistent with this, the invitation email from the Lancet suggested I “respond to [the report’s] recommendations and then raise your additional perspectives.”

I’ve written both unsolicited and invited comments many times before. All of the invited comments were accepted for publication with only minor revisions, which is pretty standard.

I didn’t reply to the first email as I wasn’t sure I had the time to write a comment. The Lancet editor followed up on this email a week later, asking again. This time I wrote back and agreed, and they sent me examples of comments they had previously published. These included “The 2020 election is a crucial opportunity to advance women’s reproductive rights,” “Announcing the Lancet commission on stigma and mental health” and “The Lancet commission on gender and global health.”

I submitted the comment on self-harm to the Lancet editor; it focused on the increases in self-harm and the possible role of social media. A few weeks later, the Lancet editors rejected it. They wrote, “We did not think the piece provided a sufficiently balanced and nuanced discussion of the evidence and issues in this area.”

This was very surprising. By definition, comments are written from a particular viewpoint. If comments are supposed to be “balanced,” why would the Lancet publish a comment about the 2020 election and abortion rights from a particular political perspective (“the role of the national government in ensuring women’s reproductive rights and justice should be a central concern for all Americans”)? Why would they publish comments like this one advocating for governments to rethink their economic priorities? And what did they think I was going to write in my comment, given my research on technology and mental health?

The only thing I can think of is that the editors wanted to publish their own comment on social media and self-harm saying social media wasn’t the cause, and my comment contradicted that. Frustratingly, their editorial on social media and self-harm made several arguments that don’t fit the data. They write: “Although rates of mental illness have gone up alongside rates of social media usage, many other ecological changes affecting young people have taken place in the past 15 years, including widening inequalities, tightening job markets, and climate change concern.”

But these trends don’t line up: Unemployment went down in the U.S. and most other countries 2010-2019 when self-harm was increasing. Job markets in 2022, when self-harm was highest, were the most employee-friendly in decades due to worker shortages. Worldwide increases in adolescent loneliness don’t covary with income inequality.

And if climate change were the cause, why would loneliness also increase among teens? How exactly would climate concerns cause loneliness? And why wouldn’t older teens and young adults, who are more likely to be aware of global issues, be the most affected, instead of tween and young teen girls?

The Lancet is seems to be arguing that 12-year-old girls are cutting themselves because they are worried about the planet warming. Isn’t it more likely they are cutting themselves because social media provides an endless way for other kids to be cruel, they can never achieve the perfect bodies they see on Instagram, they are constantly judged for their appearance in the endless selfies they are compelled to post, unknown adults can sexualize them, they are continually stressed about how many likes they’re going to get, and some social media accounts glorify (and even instruct about) self-harm? Any or all of these reasons, and more, might be why heavy social media users are more likely to self-harm.

The editors also write, “Poverty, specifically, is known to heavily influence the distribution of self-harm in all communities.” Child poverty declined 2010-2022 in the U.S., so how could it explain an increase in self-harm?

Even with the editors publishing their own comment, why couldn’t there be multiple perspectives in the journal? And if they knew they were going to write a comment themselves, why did they ask me to write one?

I don’t have answers to these questions. What I can do is publish the comment on this Substack, so you can see what the Lancet considered too controversial to grace its pages. Here it is. In particular, read the last paragraph and ask yourself: What did they consider so extreme in this conclusion that they refused to publish it, especially given other comments they have published in the past?

Social media is a likely cause of increases in self-harm: Comment on the Lancet report on self-harm

The report of the Lancet Commission on Self-Harm (Moran et al., 2024) is a major step forward in recognizing and understanding intentional self-injury and its associations with mental health issues. This is especially needed given the staggering increases in self-harm behaviors in the last 15 years, especially among girls and young women. In the U.S., emergency department admissions for self-harm behaviors doubled among 15- to 19-year-old girls and young women and quadrupled among 10- to 14-year-old girls since 2010 (see Figure 1; the increases beginning around 2010 were first identified by Mercado et al., 2017). During the same time period, self-poisonings and suicide attempts also increased among American adolescents, again especially among girls (Plemmons et al., 2018; Spiller et al., 2019).

Figure 1: Emergency department admissions for self-harm, U.S. girls and young women, by age group, 2001-2022. Source: U.S. Centers for Disease Control WISQARS database

Similar increases in self-harm among girls and young women have been documented in other countries, especially in other English-speaking countries such as the UK, Australia, and Canada (Cairns et al., 2019; Cybulski et al., 2021; Gardner et al., 2019; Patalay & Gage, 2019).

What could have caused these increases? As the report stated, there are many causes of self-harm. However, the cause of the increases in self-harm since 2010 must be something that changed in the social environment over those years – and something that changed in a similar way across English-speaking countries. That eliminates many causes that have been proposed, including the Great Recession (which ended by 2012) and school shootings (which are relatively unique to the U.S.) The cause must also be something that has a larger impact on girls and young women compared to boys and young men.

One explanation that fits these criteria is social media, which increased in popularity during the 2010s around the world in conjunction with the growing use of smartphones, a technology that allows nearly constant access to social media and the internet. Associations between social media use and low well-being are larger among girls than among boys and are particularly large among younger girls (Orben et al., 2022; Twenge & Martin, 2020). As the self-harm report notes, girls may be more subject to social comparison, bullying, and appearance judgments online than boys. Girls also spend more time using social media than boys do (Twenge & Martin, 2020).

Social media impacts adolescents at the collective level, changing the norm for adolescent social interaction from in-person to online and changing norms for appearance and status (Twenge et al., 2019). Even non-users of social media experienced a different adolescent social world in 2018 than non-users did in 2008. In addition, even individuals who spend limited amounts of time on social media may be exposed to content showing or even advocating for self-harm. Nearly half (43%) of adolescent clinical samples had seen self-harm content online (Nesi et al., 2021), and online exposure to self-harm content is longitudinally related to increases in self-harm behaviors one month later (Arendt et al., 2019).

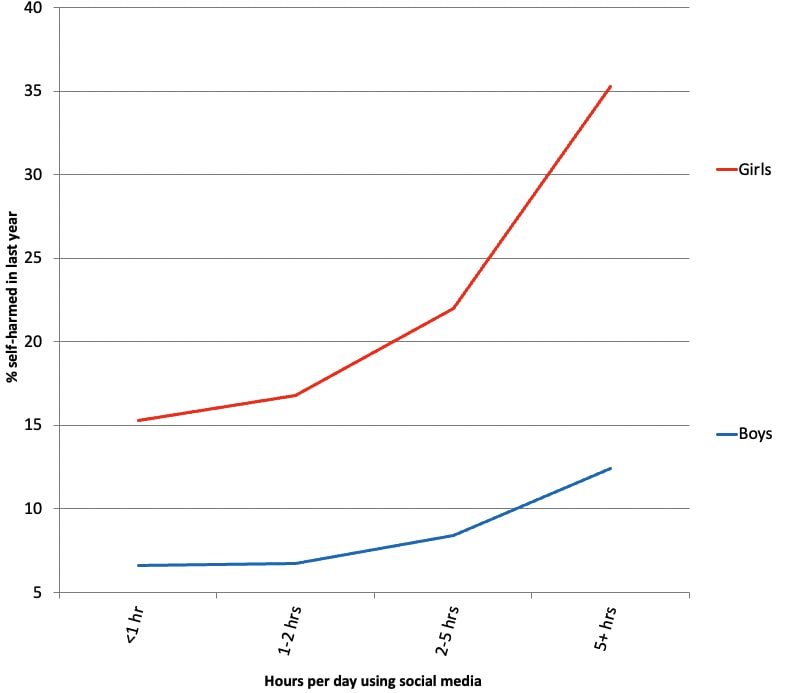

There are also associations between time spent on social media and self-harm (Tormoen et al., 2023). In one study of UK adolescents, heavy users of social media were twice as likely to have self-harmed in the last year than light users (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Percent of adolescents reporting having self-harmed in the last year by hours per day of social media use and gender, UK Millennium Cohort Study. Source: Twenge & Farley (2021)

Associations between social media use and mental health issues related to self-harm, such as depression and low well-being, are more substantial than often acknowledged in the research literature. Nearly all meta-analyses on social media use and well-being rely on linear correlation (Valkenburg et al. 2022), a statistic that does not show how many more social media users are depressed at each level of use. In contrast, a meta-analysis using relative risk (Liu et al., 2022) found that each additional hour a day of social media use increased the risk of depression by 13%, meaning that an increase from zero to 7 hours of use nearly doubles the risk of depression. That is similar to the results of studies with large sample sizes, which often find that heavy uses of social media are twice as likely to be depressed as light users (Kelly et al., 2019). Linear correlation has no established parameters for judging the strength of an association, but the size of correlations identified in scoping reviews, often around r = .10 to .15 (Orben, 2020) are similar to those identified in other studies of public health concerns. For example, the correlation between childhood lead exposure and adult IQ is r = .11 (Reuben et al., 2017). Thus, declaring similar correlations between social media use and depression “weak” or “insubstantial” seems insupportable.

Although the studies discussed thus far are cross-sectional, random-assignment experiments have also demonstrated causal links between social media use and depression. Compared to those continuing their usual levels of use, young adults randomly assigned to give up or cut back on social media use for several weeks end the time less depressed and happier (e.g., Allcott et al., 2020; Hunt et al., 2018).

Thus, although it is commendable that the report includes the online environment as a possible cause of self-harm, that contention needs further consideration of the research evidence, including the utility and interpretation of the statistics used and the inclusion of experimental studies. When this evidence is considered, the case for social media as a possible cause for the rise in self-harm becomes significantly stronger.

To be clear, social media and its accompanying effects on the adolescent social environment do not explain all cases of self-harm, which can be caused by many factors. However, the enormous increases in self-harm among girls and young women since 2010 cannot be explained by many of the usual causes of self-harm, including poverty (which has declined in most industrialized nations) or genetic predisposition (which is very unlikely to have changed substantially in 15 years). Thus, the rise of social media and related technologies must be considered as a precipitating cause of some proportion of cases of self-harm among adolescents today, particularly girls and young women.

References

Allcott, H., Braghieri, L., Eichmeyer, S., & Gentzkow, M. (2020). The welfare effects of social media. American Economic Review, 110, 629–676.

Arendt F, Scherr S, Romer D. (2019). Effects of exposure to self-harm on social media: Evidence from a two-wave panel study among young adults. New Media and Society, 21, 2422-2442

Cairns, R., Karanges, E. A., Wong, A., Brown, J. A., Robinson, J., Pearson, S.-A., Dawson, A. H., & Buckley, N. A. (2019). Trends in self-poisoning and psychotropic drug use in people aged 5-19 years: a population-based retrospective cohort study in Australia. BMJ Open, 9(2), e026001.

Cybulski, L., Ashcroft, D. M., Carr, M. J., Garg, S., Chew-Graham, C. A., Kapur, N., & Webb, R. T. (2021). Temporal trends in annual incidence rates for psychiatric disorders and self-harm among children and adolescents in the UK, 2003–2018. BMC Psychiatry, 21(1), 1–12.

Gardner, W., Pajer, K., Cloutier, P., Zemek, R., Currie, L., Hatcher, S., Colman, I., Bell, D., Gray, C., Cappelli, M., Duque, D. R., & Lima, I. (2019). Changing rates of self-harm and mental disorders by sex in youths presenting to Ontario emergency departments: Repeated cross-sectional study. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 64(11), 789–797.

Hunt, M. G., Marx, R., Lipson, C., & Young, J. (2018). No more FOMO: Limiting social media decreases loneliness and depression. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 37, 751–768.

Kelly, Y., Zilanawala, A., Booker, C., & Sacker, A. (2019). Social media use and adolescent mental health: Findings from the UK Millennium Cohort Study. EClinical Medicine.

Liu, M., Kamper-DeMarco, K. E., Zhang, J., Xiao, J., Dong, D., & Xue, P. (2022). Time spent on social media and risk of depression in adolescents: A dose-response meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(9).

Mercado, M. C., Holland, K., & Leemis, R. W. (2017). Trends in emergency department visits for nonfatal self-inflicted injuries among youth aged 10 to 24 years in the United States, 2001-2015. Journal of the American Medical Association, 318, 1931-1933.

Nesi, J., Burke, T. A., Lawrence, H. R., MacPherson, H. A., Spirito, A., & Wolff, J. C. (2021). Online self-injury activities among psychiatrically hospitalized adolescents: Prevalence, functions, and perceived consequences. Research on Child and Adolescent Psychopathology, 49, 519–531.

Orben, A. (2020). Teenagers, screens and social media: A narrative review of reviews and key studies. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 55, 407–414.

Orben, A., Przybylski, A. K., Blakemore, S.-J., & Kievit, R. A. (2022). Windows of developmental sensitivity to social media. Nature Communications, 13, 1649.

Patalay, P., & Gage, S. H. (2019). Changes in millennial adolescent mental health and health-related behaviours over 10 years: a population cohort comparison study. International Journal of Epidemiology, 48(5), 1650–1664.

Plemmons, G., Hall, M., Doupnik, S., Gay, J., Brown, C., Browning, W., & ... Williams, D. (2018). Hospitalization for suicide ideation or attempt: 2008-2015. Pediatrics, 141(6).

Reuben, A., Caspi, A., Belsky, D. W., Broadbent, J., Harrington, H., Sugden, K., Houts, R. M., Ramrakha, S., Poulton, R., & Moffitt, T. E. (2017). Association of childhood blood lead levels with cognitive function and socioeconomic status at age 38 years and with IQ change and socioeconomic mobility between childhood and adulthood. JAMA, 317, 1244-1251.

Spiller, H. A., Ackerman, J. P., Spiller, N. E., & Casavant, M. J. (2019). Sex- and age-specific increases in suicide attempts by self-poisoning in the United States among youth and young adults from 2000 to 2018. Journal of Pediatrics.

Tormoen, A. J., Myhre, M. O., Kildahl, A. T., Walby, F. A., & Rossow, I. (2023). A nationwide study on time spent on social media and self-harm among adolescents. Scientific Reports, 13, 19111.

Twenge, J. M., & Farley, E. (2021). Not all screen time is created equal: Associations with mental health vary by activity and gender. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 56, 207-217.

Twenge, J. M., & Martin, G. N. (2020). Gender differences in associations between digital media use and psychological well-being: Evidence from three large datasets. Journal of Adolescence, 79, 91-102.

Twenge, J. M., Spitzberg, B. H., & Campbell, W. K. (2019c). Less in-person social interaction with peers among U.S. adolescents in the 21st century and links to loneliness. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 36, 1892-1913.

Valkenburg, P. M., Meier, A., & Beyens, I. (2022). Social media use and its impact on adolescent mental health: An umbrella review of the evidence. Current Opinion in Psychology, 44, 58–68.

I truly fail to understand the defense of social media access and the denial of its impact. If I didn't know better, I'd like these journals are funded by tech companies.

But maybe I don't know better.

I appreciate Jean Twenge’s taking this on, but she’s getting a very important issue backwards.

The best information we have from the full 2021 and 2023 Centers for Disease Control surveys is that social media is associated with fewer suicide attempts and less self-harm among younger girls.

Twenge’s speculation that young girls’ self-harm is due to “social media” providing “an endless way for other kids to be cruel” along with harmful images and contacts happen even more in real life, except that in real life, girls can’t handle them with a <delete> or <block sender> click.

More important, social media may be an important resource helping ameliorate bullying and severe troubles inflicted by parents and household adults (see https://www.cdc.gov/yrbs/data/index.html for full survey numbers).

We need better evidence, but what we have so far paints an entirely different picture.

The CDC survey back in 2021 found that for the 1,200 girls ages 12-15 who responded, those who rarely used screens (less than 1 hour a day) suffered many more self-inflicted, suicidal injuries (6.0%) than girls who used screens 3 or more hours a day (2.6%). Girls who used screens 1-2 hours a day had the lowest rates (2.3%).

The 2023 CDC survey including 3,200 girls ages 12-15 refined these measures. Girls under age 16 who never use social media suffer many more self-inflicted injuries (6.6%) than girls who used social media once a week or less (4.9%), girls who used social media daily (4.4%), and girls who used social media many times a day (4.0%).

What, then, is causing girls to harm themselves?

Bullying (emotional abuse) by parents and/or household adults was associated with greatly increased percentages harming themselves: never-abused girls (2.6%), occasionally abused girls (2.7%), sometimes abused girls (4.7%), and frequently-abused girls (14.7%).

Further, girls whose parents, guardians, and household adults are addicted, mentally disturbed, jailed, absent, and/or frequently violent and abusive are 20 times more likely to harm themselves (6.6%) than girls in families where such troubles are rare (0.3%). Girls’ self-harm is almost non-existent in families with healthy grownups. Adults ages 25-64 suffered sharply rising drug/alcohol deaths and hospital emergencies numbering in the millions during exactly the period (2010-22) teens became more depressed.

The CDC (https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/73/su/su7304a5.htm?s_cid=su7304a5_w) reports very high associations of adverse childhood experiences led by parental/adult bullying, violent abuse, and poor mental health with 66% of teens’ sadness and 85% of teens’ suicide attempts. In contrast, the CDC analysis (like the limited Norwegian study Twenge cites that does not include parental abuses) associates social media use, school bullying, and cyberbullying with less than 10% of teens’ mental health (https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/73/su/pdfs/su7304-H.pdf), barely distinguishable from random.

Do parents have to be perfect, then? No. Very large majorities of girls in families where parents and adults occasionally are emotionally abusive or suffer troubles and normal conflicts are not depressed, suicidal, or self-harming. However, for the girls in more severely troubled families who comprise the most self-harming group, social media use is associated with fewer suicide attempts and less self harm. We should halt efforts to ban or restrict teens from social media and smartphones and study this entire question more carefully.