Who’s more pessimistic: Young liberals or young conservatives?

And which group is more likely to think voting or protesting will do any good?

Not long ago, an academic study made headlines with a polarizing conclusion: Symptoms of depression rose much more among young liberals than among young conservatives. Conservatives pounced, implying or sometimes saying outright that liberals were crazy. Liberals responded that the state of the world was so bad depression was a logical result and that conservatives were in denial. The academic article itself made a version of the argument from the liberal side, pointing to factors such as “structural racism … pervasive sexism and sexual assault … [and] rampant socioeconomic inequality.”

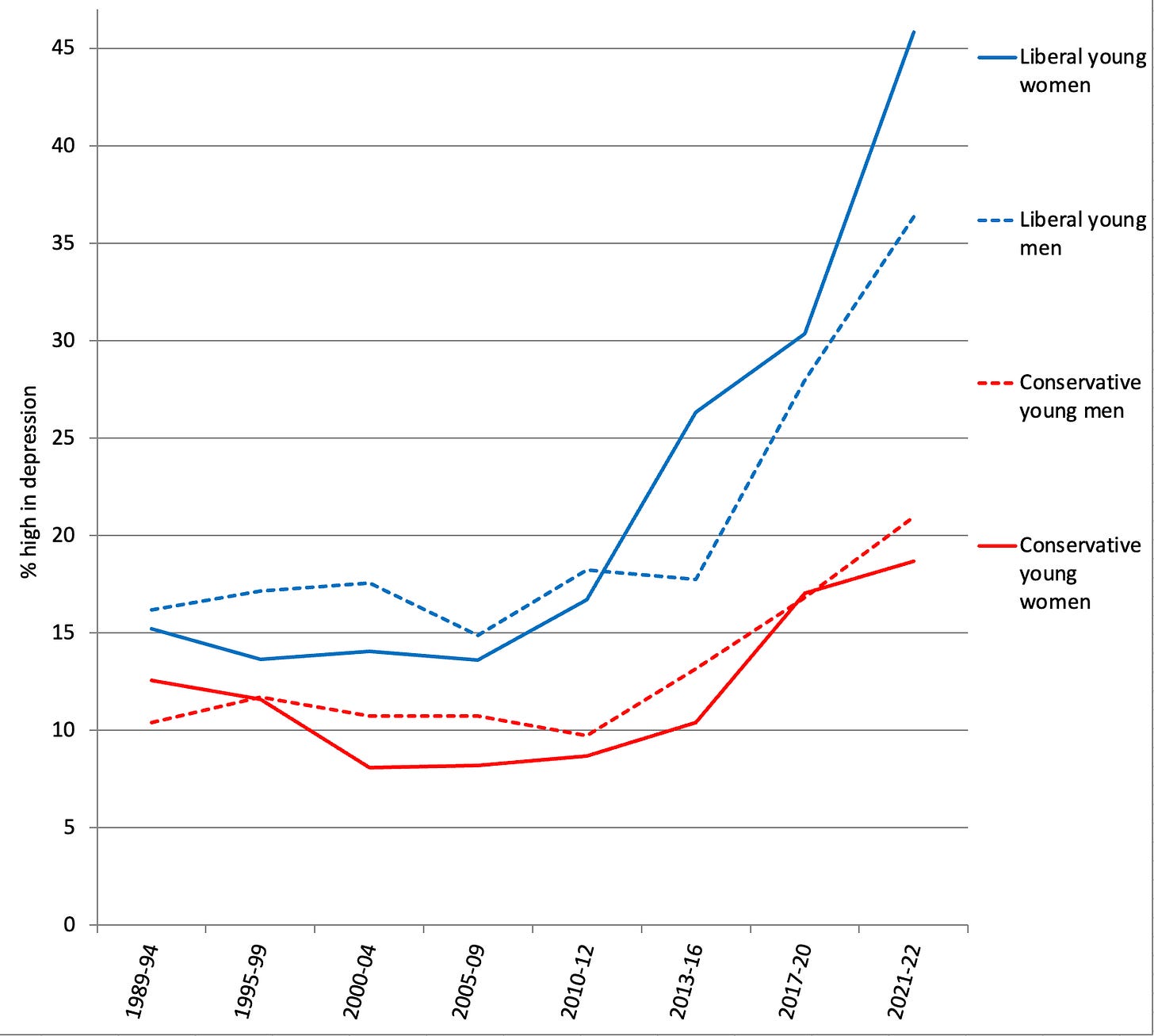

My analysis of the same variables — with updated data and a more comprehensible measure of depression — is below (see Figure 1; a version of this figure also appears in the paperback edition of Generations that will be out in January).

Figure 1: Percent of 12th graders high in depressive symptoms, by gender and political ideology, 1989-2022. Source: Monitoring the Future. Note: Depressive symptoms are measured by a 6-item measure using a 5-point Likert scale. A high score is defined as an average of 3 or higher.

While young liberals once had only slightly higher depression scores, by 2021-22 liberal young women were almost three times more likely to be depressed than conservative young women, and liberal young men almost twice as likely to be depressed as conservative young men. Plus, depression increased the most among liberal young women, where it went from 15% in the late 2000s to 46% in 2021-22 — more than tripling in a little more than a decade.

At least some of this difference is likely due to liberals spending more time on social media and less time with friends in person compared to conservatives. Beyond the “why” question, though, is the “what does this mean?” question.

With the presidential election campaign heating up, I wondered what these diverging trends mean for young voters. According Philip Bump in the Washington Post, young voters are “crucially important to Harris.” He points out that the higher proportion of younger voters in 2020 made the difference between Trump winning in 2016 and Biden winning in 2020. This presidental election cycle, for the first time, nearly all voters age 18 to 29 are Gen Z.

Thus, understanding Gen Z is key for success in this year’s elections. The trends in depression are more important than they look at first glance. That’s because depression doesn’t just involve what people feel – it also impacts how people think. By definition, depressed people see the world more negatively. They believe things are worse and are not very optimistic about things getting better.

Since young liberals are now much more likely to be depressed than young conservatives, I wondered if that also meant they were more likely to be pessimistic now. That led me to do some analyses explicitly for this post.

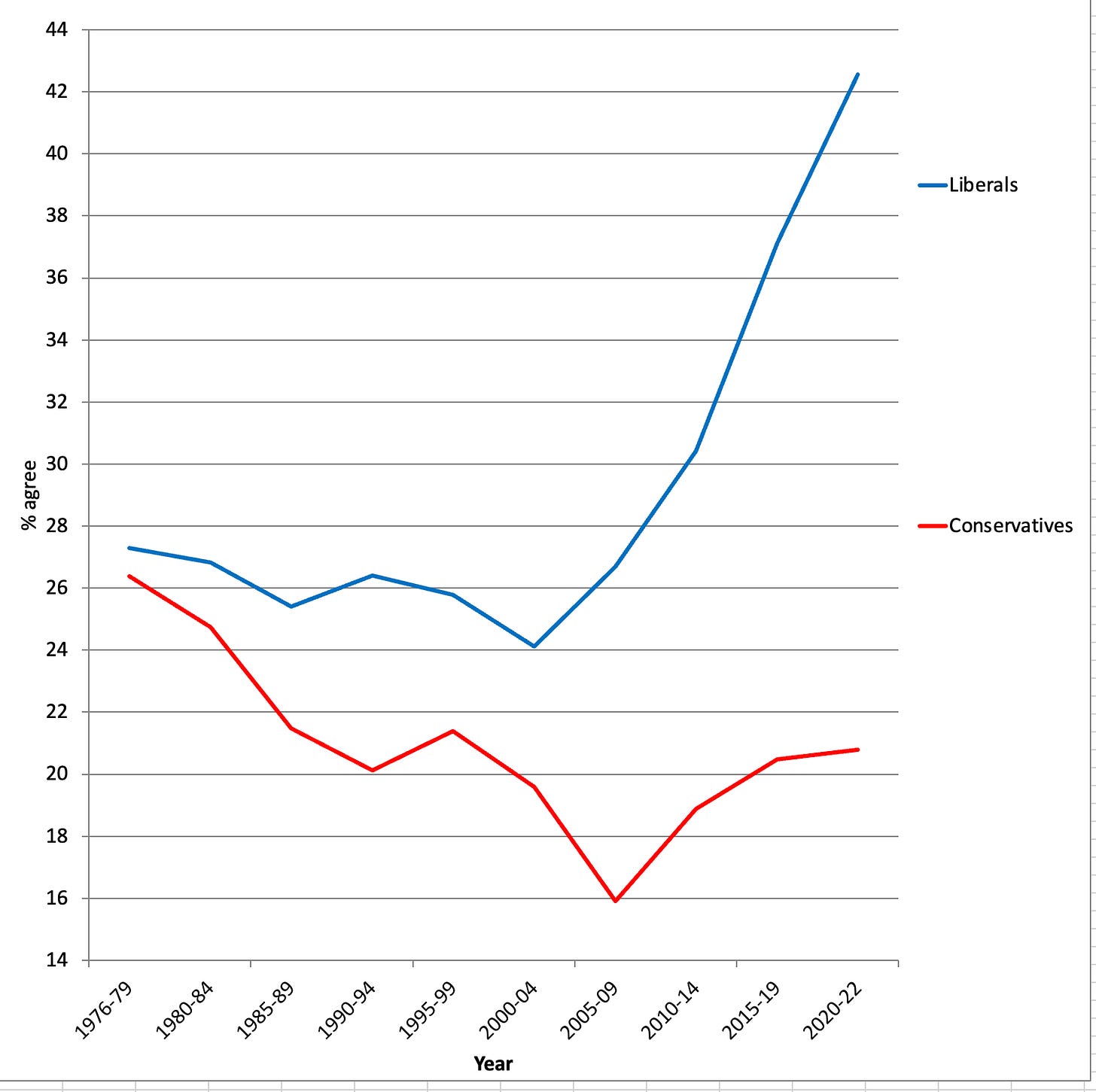

The result: While there was once a fairly small difference in pessimism between liberal and conservative young adults, a large gulf opened up with young liberals much more likely to agree with statements like “When I think about all the terrible things that have been happening, it is hard for me to hold out much hope for the world” and “I often wonder if there is any real purpose to my life in light of the world situation” (see Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2: Percent of 12th graders agreeing that they do not have much hope for the world, by political ideology, 1976-2022. Source: Monitoring the Future.

The majority of young liberals now say they have no hope for the world, compared to about a third of young conservatives. Twice as many young liberals as conservatives now wonder if there is purpose to life anymore, when the two groups once differed little in this viewpoint.

Figure 3: Percent of 12th graders agreeing that they wonder if there is any purpose to life given the world situation, by political ideology, 1976-2022. Source: Monitoring the Future.

And no, I don’t think those responses can be explained by saying “everything really is worse now.” If it’s objectively worse, why the large difference based on political ideology? There’s definitely a difference in perception, not just events. Plus, is 2024 really worse than the years of the Great Recession? Is it really worse than the early 1980s when we thought the USSR and the US were going to nuke everyone out of existence? That’s debatable. Plus, these survey questions were written in the mid-1970s. These viewpoints aren’t exactly brand new.

The content young liberals absorb online may be different from what young conservatives see. Although there’s plenty of negativity on the conservative side as well, the liberal focus on “structural racism … pervasive sexism and sexual assault …{and} rampant socioeconomic inequality” (as the academic article put it) may fuel even more negativity and pessimism.

In short, young liberals are now more likely to view the world negatively and express pessimism. That might be one reason why their votes swung toward Democrats when the nominee flipped from Biden to Harris. Since she’s not the incumbent and is younger, Harris seems more disconnected from the status quo (which, in the view of young liberals, is terrible). Campaigns should recognize that Gen Z, especially Gen Z liberals, are very pessimistic and dissatisfied and thus are looking for candidates to advocate for big changes.

That brings up another question: If young voters think things are bad, do they believe anything can be done to change that? It’s not obvious that they do. The discourse of “doomerism” online often goes hand in hand with a “what’s the point?” attitude toward voting and protesting.

So have young adults become more or less convinced that voting will do any good? And has the change been larger among liberals, or conservatives?

Believing “The way people vote has a major impact on how things are in this country” has gone in and out of fashion among young adults over the last few decades. But the 2020s brought something new: Young liberals were now just as likely to agree that voting has an impact (see Figure 4). If they put that attitude into action, young liberals may turn out at the polls this fall in higher numbers than in the past.

Figure 4: Percent of 12th graders who agree that voting can have a major impact, by political ideology. Source: Monitoring the Future.

Young liberals are also increasingly convinced that “People who get together in citizen action groups to influence government policies can have a real effect” (see Figure 5). Liberals and conservatives once differed little in their agreement that citizen action could move the needle, but young liberals grew increasingly convinced of this after 2010, reaching all-time highs in the 2020s at 3 out 4 young liberals. That suggests the uptick in protests from liberal groups will likely continue over the next decade. It also shows the increasingly large divide between young liberals and young conservatives; after 2015, citizen protest became much more the realm of liberals.

Figure 5: Percent of 12th graders who agree that citizen groups can influence government policies, by political ideology. Source: Monitoring the Future.

These trends also suggest that the gap between liberals and conservatives isn’t just about specific issues like abortion, gun control, or immigration. It’s also about whether one sees the world as mostly good or mostly bad, and whether citizens can do anything about it. Over the last 10 to 15 years, more young liberals have seen the world as mostly bad. The good news is they might be willing to do something constructive about it – if their actions follow from their words. That will be something to watch.

This seems like a dangerous setup for the future. If liberals think the world is terrible and believe they can protest their way to positive change while conservatives think the world is doing much better, conservatives may be easily convinced that liberals are going to mess up the good things in life which will just increase the antagonism between the two groups.

It would be interesting to overlay the effect of community in this analysis. I have to think that belonging to a group eases the pressure of "The world is ending." My hypothesis is that conservatives are more plugged in to faith and community groups, but it would be interesting to see the data and how that may have shifted over time.

Additionally, I wonder how the dynamics of dating among young people will change over time. Jean and others have talked a bit about this. Gen Z in general has not been dating that much. But there are real societal effects of that, and my hope is that somehow they will come to that realization in their own lives, even it is happens because they are just exhausted at being lonely and depressed.

If that happens, how will that shift the political landscape? I have seen more data that political ideology can be a deal breaker for relationships, particularly among women. But again, what is the pain threshold where these differences cease to be some important?

Maybe it is a variation on the old joke....Women's requirements for a man..

"He must be progressive"

Then after five years,

"OK, center-left will be fine"

Then after another five years,

"Center-right, but not MAGA"

etc.