Here are 13 other explanations for the adolescent mental health crisis. None of them work.

Only smartphones and social media can explain why teen depression and loneliness increased internationally after 2010.

Adolescents are in the midst of a mental health crisis. Teen depression doubled between 2011 and 2021, and 1 out of 3 teen girls in the U.S. has seriously considered suicide. U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy has described adolescent mental health as “the crisis of our time.”

As a researcher focusing on large surveys, I first started to see these trends around 2012 or 2013 – more teens said they were lonely, didn’t enjoy life, and felt they couldn’t do anything right (see Figure 6.34 in Generations). When the increases kept going, I naturally wondered what might be causing them. At the time, these surveys were also showing large shifts in how teens spent their time outside of school: Teens were spending much more time online, much less time with friends in person, and less time sleeping. That’s not a good formula for mental health, so it seemed logical these changes might be related to the increase in depression.

When I first made this argument six years ago in my book iGen, it was immediately controversial. How did we know it was phones and social media, critics asked – couldn’t it be anything? Wasn’t it possible that other cultural changes or events might be behind the increase in teen depression?

With the mental health crisis continuing, lawsuits accusing social media companies of harm to children going forward, and academic papers arguing it’s lack of independence and not technology causing the crisis, it’s a good time to consider alternative explanations for the high levels of distress among teens.

In this post, I’ll consider 13 alternative explanations for the increases in teen depression, loneliness, and suicide since 2011, including some original analyses and figures. Some explanations are easily refuted, some seem plausible at first but don’t stand up to further scrutiny, and others may work alongside smartphones and social media in causing the adolescent mental health crisis.

Alternative #1: “People are now more willing to seek help, so there’s not really an increase in depression”

This explanation is easily ruled out: The surveys showing the increase in teen depression rely on cross-sections of the whole population, not just those who seek treatment. They are designed to screen for mental health issues in a nationally representative sample. This also means the increase cannot be due to over-diagnosis, since the determination of depression is done through a report of symptoms, not directly by therapists or doctors.

Alternative #2: “More teens are OK with saying they are not OK”

Perhaps teens have become more likely to admit to having symptoms of depression on anonymous self-report surveys, and that’s why rates of depression have increased.

If so, there would be no changes in behaviors related to mental health, since objective measures of behavior are not self-reported. However, behavioral measures show increases nearly identical to those in self-report. For example, emergency room admissions for self-harm have nearly doubled for 15- to 19-year-old girls and have quadrupled for 10- to 14-year-old girls (see Figure 1). The suicide rate for these age groups has also doubled or more (see #10, below) – something else that can’t be explained by self-report changes.

Figure 1: Rate of emergency room admissions for self-harm behaviors among U.S. girls and young women, by age group. Source: CDC (also see Figure 6.36 in Generations)

I also don’t know of a single study that shows teens are now more willing to self-report symptoms of depression than in the past (If you know of one, though, please let me know!) This is said all the time, but there is no empirical evidence for it, to my knowledge.

Alternative #3: “It’s because of the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdowns”

This is easily refuted: The increases in teen depression began in the early 2010s, at least 8 years before the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic certainly didn’t help, but it was definitely not the origin of the problem. Despite this, many news stories assume the pandemic is the cause.

Alternative #4: “It’s the economy, stupid”

This alternative argues that the Great Recession caused the rise in teen depression. In fact, indicators of a poor economy (such as unemployment) were decreasing when teen depression was rising 2012-2019 (see Figure 2). That’s when the U.S. economy finally roared back after the recession of the late 2000s.

Figure 2: Technology adoption, teen depression, and national unemployment, 2006-2019. Sources: National Survey of Drug Use and Health, Monitoring the Future, Pew Research Center, Bureau of Labor Statistics. See also Figure 6.39 in Generations.

What does line up? Smartphone ownership, social media use, and time online.

Alternative #5: “Social media’s impact is too small to have caused the rise in depression”

This one is more complicated, but just as wrong as the first four.

An article in New York Magazine made this argument: “the correlation isn’t strong enough to explain more than 4 percent of the variance in girls’ mental-health levels — which is to say, even if we accept [Twenge and Haidt’s] account, some additional, complementary factors are likely necessary for explaining the scale of the increase in rates of teen depression and suicide in recent years.”

That’s not how this works. First, the “percent of the variance” calculation is misleading both statistically and practically (David Funder and Daniel Ozer explain why here). This discredited statistic doesn’t even answer the right question. We want to know why depression increased so suddenly, not how much social media might matter in the universe of all causes – including the largest, genetic predisposition, which cannot possibly have changed in a decade.

But, for the sake of argument, how big is the link between social media use and depression among individuals? The statistic in the New York Magazine article is from a study showing that the two correlate about r = .20 for teen girls. That is a positive correlation, so the more hours a day a teen spends on social media, the more likely it is that she will be depressed.

But how much more likely? In this dataset, girls spending 5 hours a day or more on social media were three times more likely to be depressed than non-users, and boys who were heavy social media users were twice as likely to be depressed. Assuming even some of that is causal, it certainly seems large enough to explain a good chunk of the increase in depression, given the increases in social media use over the years.

It’s also not small from a practical point of view: If teens who ate 5 apples a day (vs. none) were three times more likely to be depressed, parents would never let their kids eat that many apples – and they’d probably outlaw apples entirely from their children’s diet.

Time spent on social media also isn’t the only factor. Some teens might feel depressed from, for example, looking at Instagram’s perfect bodies after only a short amount of time.

Plus: Social media doesn’t just operate at the individual level. Because it is a communication tool used by groups of people, it impacts even those who don’t use it. If a teen girl decides not to use social media and tries get together with her friends more frequently – as if it’s 1988 again – she’s unlikely to be successful. The norm for social interaction changed even for the few teens who resisted social media or used it sparingly.

With the combination of both individual-level and group-level effects, digital technology and its displacement of in-person social interaction and sleep is large enough.

Alternative #6: “It’s because children and teens have less independence”

A recent paper getting lots of attention on Twitter/X argues that the mental health crisis is caused by children and teens having less independence than they used to.

Of all of the alternatives thus far, this one may come the closest to being right – with a few caveats.

It is definitely true that children and teens are less independent now – kids are less likely roam their neighborhoods and play independently, and teens are now less likely to have their driver’s license and go out with their friends (see Figures 6.16, 6.17, and 6.45 in Generations).

The paper curtly dismisses the idea that social media and smartphones might have anything to do with the mental health crisis. That’s strange, because the trend away from independence dovetails with the impacts of digital media in many ways: Both, for example, lead to teens spending less time with friends in person.

But teen depression did not increase suddenly when teens became less independent, a trend that began in the 1990s to early 2000s. Figure 3, made just for this post, zooms in on the period 1989-2011. Even though fewer 12th graders got their driver’s license, dated, or went out with friends – and thus teen independence was on the wane — depressive symptoms did not change much (especially compared to the rise after 2011; see Figure 2).

Figure 3: Lack of independent activities (12th graders), high depressive symptoms (12th graders) and clinical depression rates (16- to 17-year-olds), U.S., 1989-2011. Sources: Monitoring the Future and the National Survey of Drug Use and Health.

Teen depression only began to skyrocket after smartphones and social media entered the scene in the early 2010s, with teen independence continuing its slide in that era. If the party is on Snapchat, who needs a driver’s license or to go out? The two trends are likely reinforcing each other.

Notably, the decline in teen independence has also coincided with declines in alcohol use, sex, and pregnancy among teens – trends that are very positive for teen well-being, unlike the decline in going out with friends. Yet these trends are all related: Being independent, going out, driving, having sex, and getting pregnant are all things adults do and children don’t.

So teens are putting off doing adult things, with both positive and negative outcomes – as I argue in Generations, it’s part of the slow life strategy that occurs because people now live longer lives. A slower life doesn’t necessarily mean more depression if teens postpone some of the challenges of adulthood (like dating, alcohol, and sex) for later. But combine that with an even higher level of social isolation caused by digital technology, and add in sleep deprivation, and that’s a formula for depression.

Alone, the decline in teen independence doesn’t work that well to explain the rise in depression. Combined with the rise of smartphones and social media, it does.

One more note, which is speculative: Perhaps the decline of independence has the biggest effect on mental health not during childhood but during late adolescence and young adulthood. Teens now graduate from high school with less experience with independence, so when they get to college and/or the workplace they find it more difficult to make decisions on their own. That’s why so many colleges “coddle” their students, and why so many parents step in to solve the problems of their college-age offspring. But if that help is not enough, young college students may struggle, leading to depression.

Alternative #7: “It’s because of school shootings”

At first, this seems somewhat plausible: After all, the horrific Sandy Hook school shooting happened in 2012.

However, school shootings first became a concern much earlier, in the 1990s – a time when teen depression was steady or, in some datasets, actually improving. Columbine happened in 1999, for example.

The big nail in the coffin is this: Teen anxiety and loneliness increased not just in the U.S. but in other countries that do not have school shootings at the rate that the U.S. does (see Figure 4, made for this post, and my previous post on increases in teen anxiety around the world). Yet the increase is just like the one in the U.S., beginning around 2012.

Figure 4: Percent of teens who are lonely at school, by country, 2000-2018. Source: PISA survey; Twenge et al (2021) NOTE: The PISA survey is done every 3 years. The loneliness items were not asked in 2006 and 2009.

Alternative #8: “It’s because of climate change” (and its twin “It’s because we live in a postmodern hellscape”)

This one seems somewhat plausible at first as well. But:

-- If climate change were the cause, we’d expect the largest increases in depression, self-harm, and suicide among young adults, or perhaps older teens, who are more likely to be politically and socially aware. Instead, the largest increases are among younger groups (for example, the increase in self-harm is largest among 10- to 14-year-olds — see Figure 1 here).

-- Concern for the environment peaked in the 1990s among teens, not in the 2010s (see Figure 4.34 in Generations). Concerns around climate change were prevalent long before 2012 (including in the mid-2000s when An Inconvenient Truth was released).

-- As Jon Haidt points out in his excellent upcoming book, The Anxious Generation, when young people come together over a cause, they usually become energized, not depressed. Emile Durkheim’s classic study of suicide found lower suicide rates during times of trouble, not higher.

Then there’s what I call “the hellscape narrative,” usefully summarized here by Millennial journalist Taylor Lorenz, who tweeted in February 2023: “People are like ‘why are kids so depressed it must be their PHONES!’ but never mention the fact that we’re living in a late stage capitalist hellscape during an ongoing deadly pandemic w/ record wealth inequality, 0 social safety net/job security, as climate change cooks the world.”

Although it’s certainly true that we have big problems to solve, it’s also fair to ask: Is right now really worse than March 2020 at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic? Is it really worse than 2008 when the financial system was on the verge of collapse and home foreclosures spiked? Is it really worse than during World War II? Is it really worse than the early 20th century, when the infant mortality rate was 10 times higher than it is now?

Every generation and every time has its challenges, but whether the reaction to those challenges is action or nihilism is more about perception and psychology.

Alternative #9: “It’s due to increased academic pressure and too much homework”

This idea has been mentioned frequently lately, including by Derek Thompson in the Atlantic, New York Magazine, and by teens interviewed by the Associated Press. These stories often specifically mention that teens have much more homework than they did in the past.

Except they don’t. By U.S. teens’ own reports, they actually spend less time on homework now than teens did in the 1990s (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: Minutes per day spent on homework, U.S. 8th and 10th graders, 1992-2021. Source: Monitoring the Future

A recent Gallup poll also belies this idea of overly burdensome homework hours, showing the enormous discrepancy between the large number of teens who spend 2+ hours a day on social media compared to those who spend the same amount of time on homework (see Figure 6). In Gallup’s data, the average teen spends about 5 hours a day on social media, which completely dwarfs the hour or so they spend on homework.

Figure 6: Percent of U.S. teens who spend two or more hours a day on certain activities. Source: Gallup report

American teens are also less likely to say that there is a lot of competition for grades at their school, suggesting academic pressure has not ramped up in recent years (more here in an earlier post).

In a recent paper, my colleagues and I did find that self-reports of school pressure (mostly among European teens) increased at the same time as teen anxiety. However, increases in internet use were more closely linked to the rise in anxiety than school pressure. In addition, self-reported school pressure is subjective, and anxious people are more likely to feel under pressure, so the causation might be reversed.

Alternative #10: “Suicide rates were higher in the 1990s when there was no social media, so this is just part of a cycle”

This argument was summarized in a Substack post by Will Rinehart and Taylor Barkley. The idea is that teen suicide rates (and thus presumably teen depression) go through cycles – at some times the rates are high, and others low, and no one really knows why. A few important points:

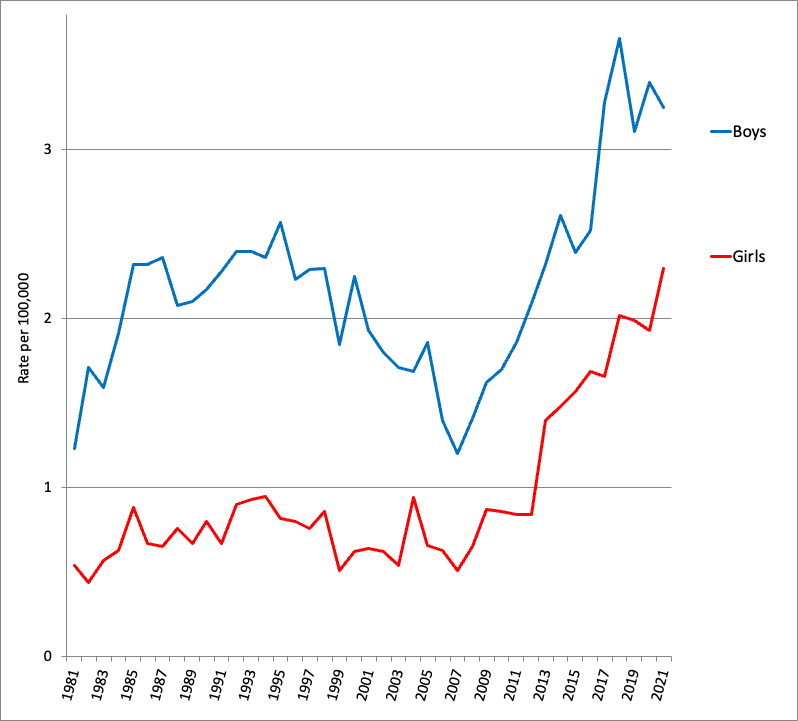

-- Rinehart and Barkley’s graph appears to have incorrect data for the years 1999-2020. When I tried to verify their numbers using both the CDC WIQARS and WONDER databases, I was able to do so for their data up to 1998, but not 1999-2020. I suspect they inadvertently had a filter on when they extracted the data for these years. Figure 7 shows the correct suicide statistics for teens and young adults, and Figure 8 for 10- to 14-year-olds.

Figure 7: Suicide rate, U.S. 15- to 24-year-olds, by age group, 1981-2021. Source: CDC

Figure 8: Suicide rate, U.S. 10- to 14-year-olds, by gender, 1981-2021. Source: CDC

The suicide rates of 10- to 14-year-olds and 20- to 24-year-olds in 2016-2021 are considerably higher than they were in 1988-1994. For these age groups, then, the statement “suicide rates were higher in the 1990s” is not true. Suicide rates are higher now.

The suicide rate for 15- to 19-year-olds in 2017 and 2018 exceeded any previous rate on the chart. The 2021 rate exceeded all but 4 previous years. The average suicide rate 2016-2021 among 15- to 19-year-olds was 10.81; for 1988-1994 it was 10.96 – essentially the same. So suicide rates were only marginally higher in the Gen X era compared to now.

-- Does that prove that social media doesn’t have anything to do with it, since there was no social media in the 1990s? Of course not. Different times have different environmental influences on suicide rates. The late 1980s and early 1990s were a terrible time for teens, with record rates of violent crime and teen pregnancy. As I found in Generations, the increase in teen and young adult suicides was due to the availability of cheap guns – and it almost exactly paralleled the rise in homicides during the same era. That’s one reason why the high suicide rates of the 2010s are so surprising: Those were years with markedly lower homicide rates. Overall, the 2010s were much better for teens, with lower rates of violence and teen pregnancy — yet suicide rates were just as high or higher than in the rough early 1990s.

Alternative #11: “It’s because teens don’t have places to hang out anymore”

According to this theory, teens have been chased out of the places they used to hang out, like malls and public spaces, and that’s why they don’t get together with each other in person anymore.

This theory has more credibility than some, as it’s true many municipalities cracked down on teens hanging around public spaces in the last few decades. However, that didn’t happen all at once in the early 2010s – it had been going on for a long time. Compare that to smartphones and social media, where the changes were much more sudden.

Plus, the decline in teens getting together in person is very broad and consistent. It’s not just declines in going to malls, for example. It also occurs for “getting together with friends informally,” which can be done at home as well. It also occurs for going to parties, most of which are also held at private homes. Also, with teens spending 5 hours a day on social media, when are they going to find the time to hang out in person?

Alternative #12: “It’s because of the opioid epidemic”

The increase in opioid deaths is primarily among middle-aged people, not teens. Yet kids and teens are the group with the largest increases in depression and self-harm. Opioid deaths are also very regional, with large increases in some areas of the country and little in others. In contrast, the increase in teen depression was nationwide.

Alternative #13: “Parents are more depressed and troubled”

The New York Magazine article theorizes that perhaps the parents of kids and teens are more depressed and have passed this down to their children.

Except they aren’t. While teen and young adult depression have skyrocketed, the rate of depression among those ages 35 to 64 (the age groups most likely to be the parents of teen children) has stayed about the same (see Figure 9).

Figure 9: Percent of U.S. adolescents and adults with major depression in the last year, 2005-2021. Source: National Survey of Drug Use and Health.

Of all of the alternative explanations, only #6 (declines in independence) stands up to scrutiny when examined, and it seems to be working together with the rise of smartphones and social media, not against it. If the decline in teen independence had occurred in the absence of smartphones and social media, it may have led to somewhat higher rates of depression. But if teens were still seeing friends in person about as much, were sleeping just as much, and were not on social media 5 hours a day — all things traceable to the rise of smartphones and social media — I highly doubt teen depression would have doubled in a decade.

As always, your thoughts welcome in the comments: What do you think of these alternative explanations? What are some I haven’t considered here?

There’s no doubting the harmful effects on children due to the loss of independence and unsupervised outdoor play (point #6), as I point out at length in my book “Life Before the Internet”.

But this cannot be separated from smartphones and social media, and here’s why.

Before the arrival of the iPhone in 2007, the internet was just a tool. You had to go and find a computer, sit down in front of it and log on. And when you were done, you left and got on with the rest of your life.

This advent of smartphones completely upended this reality by putting the internet in one’s pocket. We now no longer had to go and find a computer, sit down in front of it and log on. We just had to pull our phone out of our pocket. Suddenly, the internet spilled over into our previous everyday activities and changed our lives forever. The idle time we used to spend playing outside, socializing and reading, soon gave way to social media. And the rest is history.

Brilliant and helpful. Appreciate the “dialogue” between Gray’s work and your own.