Is child abuse the real reason for the teen mental health crisis?

We finally have a definitive answer

With the adolescent mental health crisis still continuing, it’s even more crucial we find out what’s causing it. Why are teens today twice as likely to be depressed as teens in 2011?

When I first started to see these trends in the mid-2010s, I had no idea what might be causing them. With teen depression increasing even as the economy improved, it was clear it wasn’t economic cycles. It’s also not too much homework. With loneliness increasing just as much as depression, it’s not climate change — why would climate change increase loneliness? I’ve been able to rule out or partially rule out many, many other explanations that just don’t fit the data the way that smartphones and social media do.

One alternative explanation for the rise in depression was difficult to fully rule out (or in, for that matter) – child abuse. In a previous post, I found a few reports suggesting child abuse was either unchanged or down, but at the time I wasn’t aware of a source that had data on child abuse, particularly of adolescents, across several decades.

If more parents and guardians were physically hurting teens, that would certainly explain an uptick in teen depression, anxiety, and loneliness. That’s the contention of some writers who contend that the real problem for adolescents today is that parents are abusing them. In that previous post, I found that the CDC survey he used in this article changed its measurement over the years and thus doesn’t actually show an increase in the abuse of teens.

To really consider this explanation, though, we need a source with consistent measurement of child abuse over the decades from a reliable, nationally representative survey. And I finally found one: the National Crime Victimization Survey, administered by the Bureau of Justice Statistics, which is part of the U.S. Justice Department.

The NCVS has a dashboard where you can examine data going back to 1993. It includes a variable called “victim-offender relationship” where the choices are intimate partners, well-known/casual acquaintances, strangers, and other relatives. For adolescents, “other relatives” is mostly going to be parents, step-parents, and legal guardians, maybe a few siblings. If there’s been an increase in child abuse since 2011, this is where we’d find it.

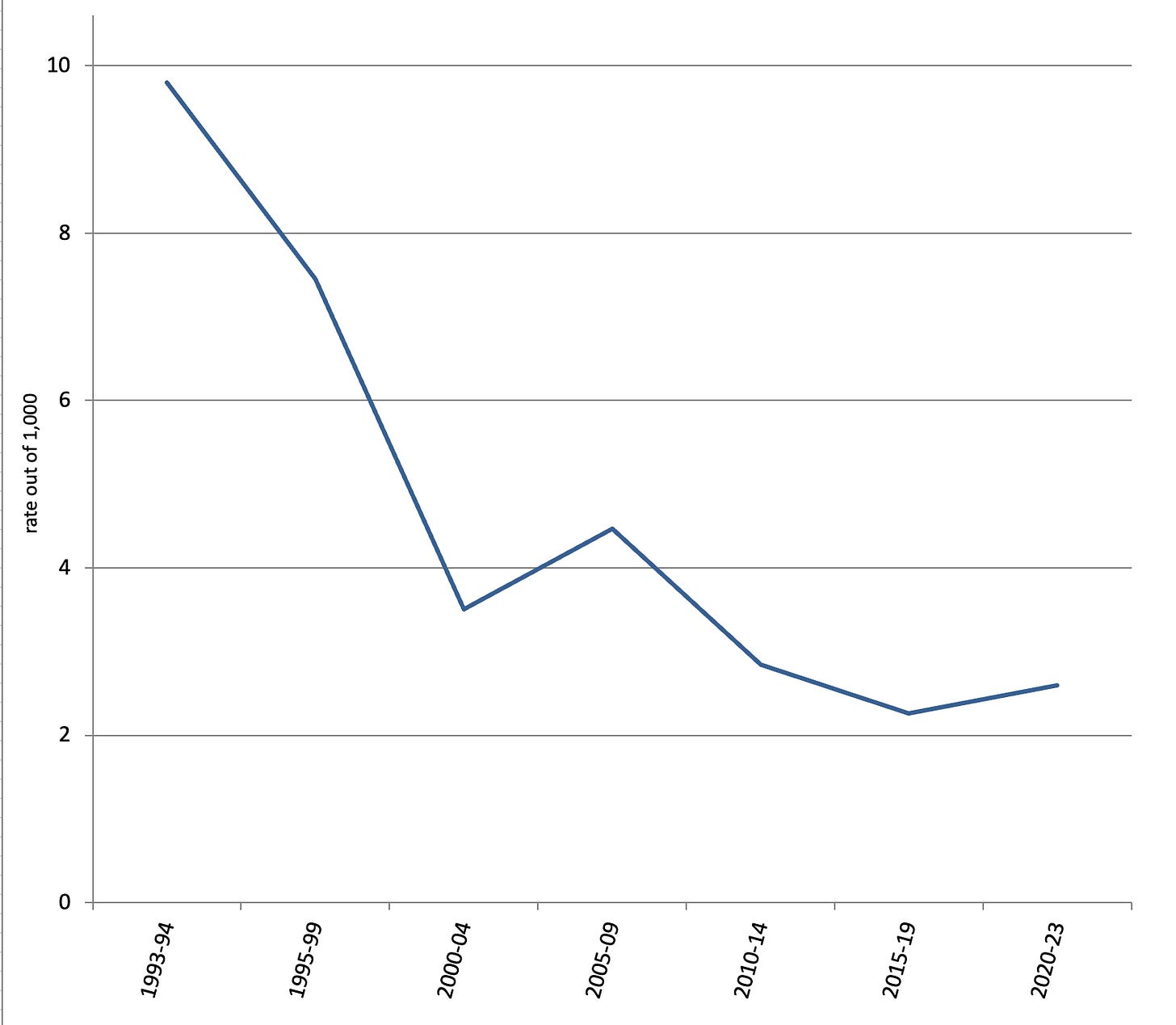

Instead, rates of violent victimization of adolescents by parents are down — by a lot. In the 2020s, abuse of teens by family members was only about a fifth of what it was in the mid-1990s. Over 2010-2023, when teen depression doubled, victimization rates stayed at about the same very low rate – about 2 out of 1,000, or .2%. That’s a fifth of one percent. For comparison, 28% of adolescent girls in the U.S. were clinically depressed in 2022.

Figure 1: Rates of violent victimizations of 12- to 17-year-olds by relatives, 1993-2023. Source: National Crime Victimization Survey. NOTE: Shows the mean for 12- to 14-year-olds and 15-to 17-year-olds.

This is very good news – fewer teens are being victimized by parents or other relatives. That’s consistent with the overall decrease in crime rates and the decrease in the teen homicide rate over this period. Teens are also less likely to get in physical fights now compared to past decades.

In other words, fewer teens are victims of violence either at home or away from home. Yet twice as many are depressed, clearly suggesting that something else is wrong. They’re not being victimized by their families — they’re being victimized by the compulsion to spend almost all of their leisure time with screen media.

By the way, Dr. Twenge's NCVS trends are entirely dependent on the way she groups years. If we look at annual NCVS numbers the way she reports, say, annual teen suicide numbers (which are vastly smaller), the opposite conclusion can be shown for the rate of violent victimizations of teens age 12-17 by relatives:

1.5 in 2011 per 1,000 population age 12-17

1.8 in 2018

3.1 in 2021

3.3 in 2022.

That is, family abuses of teens skyrocketed during the 2011-22 period, exactly the time teens' depression also rose. Subjective presentations of tiny numbers can be shuffled around to show any result desired.

I’m sorry to post three times on Dr. Twenge’s substack challenging my article, but I examine critiques of my work carefully. I want my errors pointed out so I can fix them.

In this case, however, further examination shows the entire premise of Dr. Twenge’s argument is wrong. Her and her colleagues’ such as Jonathan Haidt, and Zach Rausch’s baseless dismissals of parents’ and grownups’ widespread violent and emotional abuses victimizing teenagers, as well as parents’ and caretakers’ depression, addiction, and criminal behaviors, is endangering young people and needs to stop.

First, the NCVS she cites is a useless measure of family violence against teenagers, one I will no longer cite. The reason: five-sixths of the interviews of teens by the NCVS are conducted in the presence of others (primarily parents). Unsurprisingly, these chaperoned teens are vastly less likely to reveal family violence than the one-sixth of teens interviewed in private (see research institute analysis, https://ww2.amstat.org/meetings/proceedings/2015/data/assets/pdf/233894.pdf ). This is why anonymously-conducted surveys like the CDC’s uncover far higher parental and adult violent abuses of teens than the NCVS.

Second, even if we accept Dr. Twenge’s measures, she uses the wrong time period (teens’ depression actually rose from 2010 to 2021 and fell in 2022 and 2023 (it’s also unclear why she graphs the irrelevant 1993-2009 period). She then aggregates the NCVS data into unwieldly 5-year periods that mask the true trend.

Substituting the standard method of determining a trend – in this case, plotting the annual NCVS rates of violent family abuses of 12-17 year-olds and calculating a regression trendline that incorporates all the data – shows that violence by family members victimizing teens rose by a substantial 44% over the 2010-21 period, exactly the time teens reported becoming more depressed.

Finally, even though the 32% of teens (35% of girls, 29% of boys) in the CDC’s definitive 2023 survey who report histories of violent victimization ("hit, beat, kicked, or hurt you physically") by parents and household adults are many times more likely also to report being depressed, sad, suicidal, and self-harming, I don’t argue that family violence is the main factor driving teens’ poor mental health. Parental and adult violence victimizing teens is too closely intertwined with the far larger factor of parental/adult emotional abuse to show up separately.

We already know from extensive analyses of dozens of studies by all sides that while social media use creates problems for a small fraction of teens and adults, social media is a negligible factor in teens’ poor mental health overall. I don’t understand on what grounds Dr. Twenge keeps dismissing parental/adult emotional and violent abuse while insisting the problem is just teens using screen media.