The homework bubble has popped

Middle and high school students are suddenly spending less time on their schoolwork even as more are getting A’s

Contrary to popular belief, teens didn’t change suddenly during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, depression, unhappiness, and loneliness started to spike in the early 2010s, about 8 years before the pandemic. Many other trends (like the decline in trust and decrease confidence in institutions) had been building for decades.

There are two big exceptions to the “no sudden changes” rule for the pandemic era. One is work ethic, which slid rapidly in 2021, 2022, and 2023. Eighteen-year-olds became much less likely to say they were willing to work overtime or to believe that work would be a central part of their lives.

The other is time spent on homework. I’d previously looked at trends in homework after some researchers suggested that too much homework might be the cause of the increase in teen depression. That analysis found that U.S. 8th and 10th graders’ homework time had actually gone down over the decades .

However, that analysis had data only up until 2021. The data for 2022 and 2023 is now available – and it shows a sudden change.

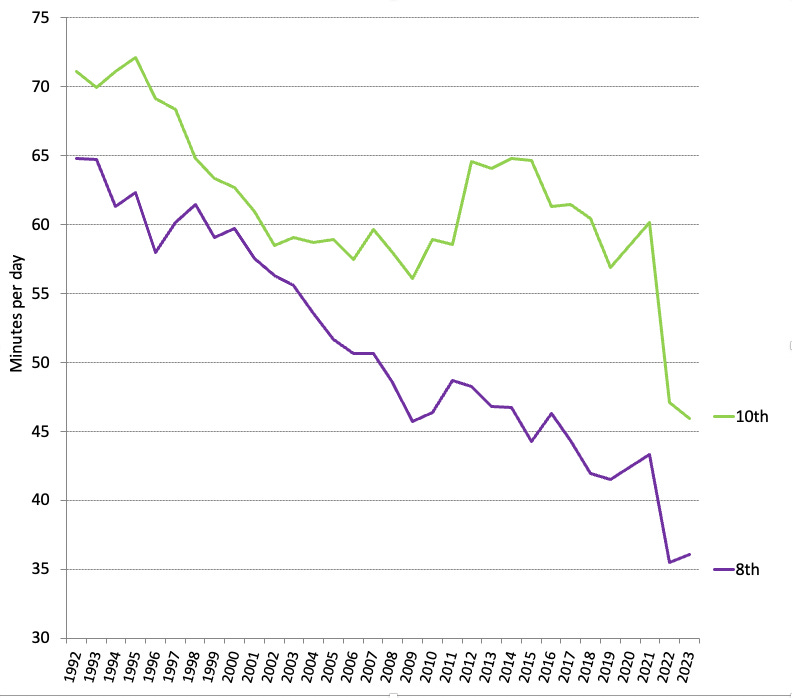

Tenth graders’ average homework time plummeted by nearly 15 minutes a day from 2021 to 2023 (see Figure 1). That’s a 24% decline in homework time in just two years. Eighth graders’ homework time dropped by 7 minutes a day, a 17% decline.

Figure 1: Minutes per day spent on homework, U.S. 8th and 10th graders, 1992-2023. Source: Monitoring the Future

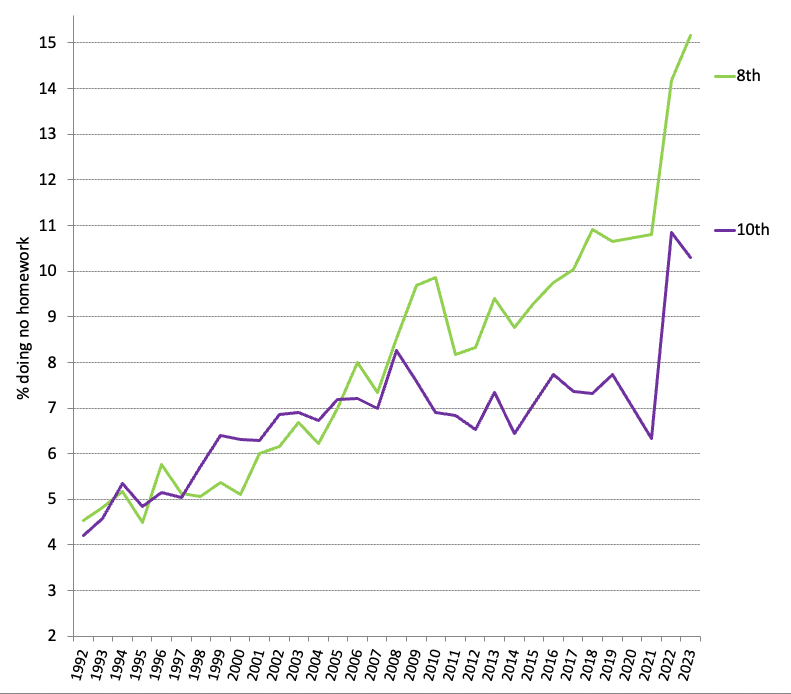

Not only that, but the number of students who say they do no homework at all suddenly spiked. For 10th graders, it’s gone from 6% in 2021 to 10.3% in 2023. For 8th graders, 15.2% now do no homework at all, up from 10.8% in 2021 (see Figure 2). A growing number of students are doing no schoolwork at all outside of school hours.

Figure 2: Percent of U.S. 8th and 10th graders who do no homework at all, 1992-2023. Source: Monitoring the Future

What’s going on here? Why are teens spending less time on homework – and why are so many more not doing it at all?

Let’s consider the possibilities. Here are a few:

1. Students spent less time on homework because they were using AI & ChatGPT to do their assignments. Homework time started to decline in spring 2022, so ChatGPT, which didn’t go online until late November 2022 and didn’t become popular until January 2023, can’t be responsible for the trend’s origin. AI might have something to do with the continued lower homework time in 2023, though.

2. Teachers assigned less homework. That could be. Maybe teachers are burned out post-pandemic, or they think their students don’t need to do as much homework. But with homework time less than an hour a day even before the decline, this seems unlikely.

3. Teachers were assigning just as much homework, but students were refusing to do it – or at least weren’t doing it as well. That’s possible. In the same dataset, students also became increasingly likely to say they weren’t willing to work overtime in their future jobs. The post-pandemic era has seen a reconsideration of work – and for 8th and 10th graders homework is work. But with homework time already low, that explanation seems less likely.

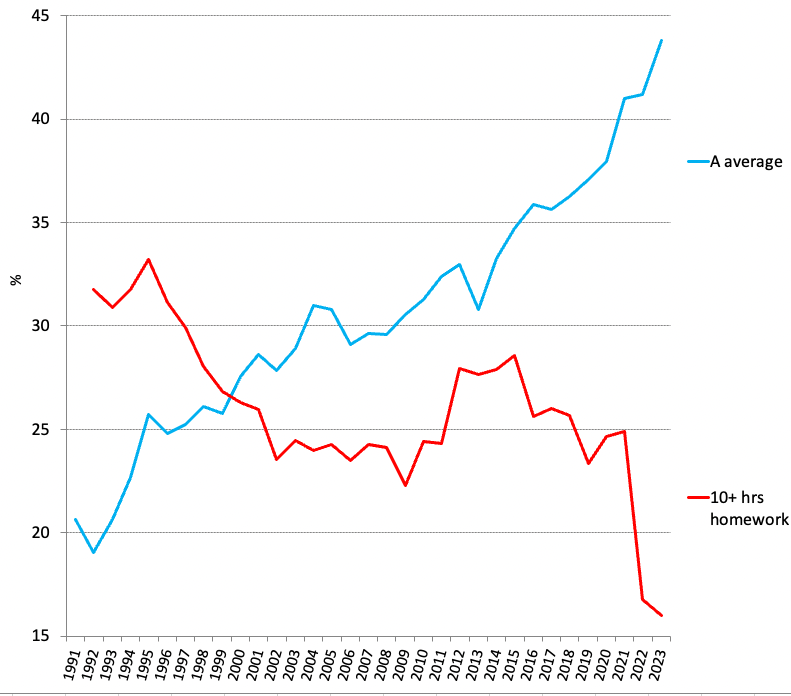

Another strike against this idea: Grades have not gone down – in fact, they have gone up. Even as the number of 10th graders spending 10+ hours a week on homework plummeted in 2022 and 2023, the number with an A average reached all-time highs (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Percent of U.S. 10th graders with an A average and percent doing 10+ hours of homework a week, 1992-2023. Source: Monitoring the Future

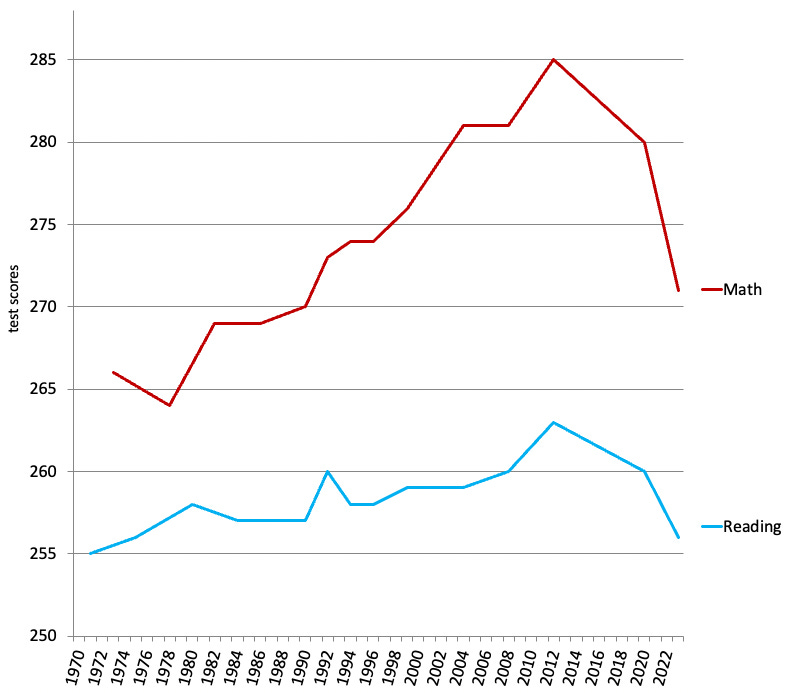

4. Students are smarter – they can do better work in less time. That’s unlikely, since students are not performing better academically. In fact, they are performing considerably worse. Scores on standardized tests, like those administered by PISA and NAEP, have gone down since 2012 and especially into 2022-23 (see Figure 4). After improving for decades, math and reading skills have declined, suggesting students are now learning less.

Figure 4: Math and reading scores, U.S. 8th graders, 1971-2023. Source: National Assessment of Educational Progress (the Nation’s Report Card)

5. Both students and teachers have given up. Students are doing less work but getting better grades. That suggests that teachers are lowering their standards for A grades. Students have given up on doing hours of homework, and teachers have given up on holding students to high standards. In my view, this explanation – sadly – fits the data the best.

Reports abound of teachers quitting after the double whammy of smartphones and COVID. Mitchell Rutherford, a high school biology teacher from Arizona, said students put on headphones in the middle of class, saying it eased their anxiety. They told him they didn’t want to be at school. By October, half of his students were failing. Rutherford quit at the end of the school year. “Part of me feels like I’m abandoning these kids. I tell kids to do hard things all the time and now I’m leaving?” he said. “But I decided I’m going to try something else that doesn’t completely consume me and drain me.”

I’d love to hear your take on this – why are students spending less time on homework? And why are more getting As when objectively measured performance is down?

#5

As a mom whose first born child entered the public school system (for transitional kindergarten) in August of 2020, I have witnessed the failings of ed tech and the deleterious effects of an attention economy on our kids, which have obviously been amplified by the pandemic. I have been an in-classroom parent volunteer for 4 years at my daughter's public school (kindergarten, 1st, 2nd and now 3rd grade) and was initially shocked by how little teachers are actually able to teach due a significant portion of children not being able to focus. Last year my daughter's second grade class had such a large number of students (all boys) who were disruptive that the teacher was assigned a Behavioral Interventionist to work full-time in the classroom. I witnessed one boy unable to recite the Pledge of Allegiance because he couldn't take his eyes off the Youtube video he was watching on his Chromebook. Another student would shout out expletives when he couldn't get his Chromebook to function as desired. I once asked him what his favorite thing to do on the weekend was and he cited watching LankyBox videos on YouTube and buying LankyBox "merch" at Target. This year, I've observed my daughter's current third grade teacher basically give up teaching math and resort to turning on a video because the kids struggle so much with it and are unable to sit and focus. It's sad and foreboding. I don't fault the teachers. It's a current that's almost impossible to swim against. If kids aren't being taught to focus and learn at home, there's no way teachers are going to be able to enforce the practice in and from the classroom, especially public school educators.

I am a high school social studies teacher, and I have stopped assigning regular homework. I was putting so much time and effort into creating assignments that couldn't be cheated on, and it was exhausting. I gave up. I still have students read one narrative nonfiction book of their choice in my U.S. history course. The assessment is to have a conversation with me about it. Faced with that, several students opted to simply not do it.