Is social media use beneficial for marginalized groups?

If so, more social media should equal less depression for Black and Hispanic teens. Does it?

“But aren’t there benefits to social media use, especially for marginalized groups?”

This question comes up quite a bit in discussions of teen social media use. For example, the idea that marginalized teens benefit from social media has been used to argue against legislation restricting social media use among teens. One commentator argues that “culturally diverse teens greatly benefit from social media.” If so, we would expect that these groups would have better mental health the more frequently they used social media.

But this argument founders against the trends in teen mental health. If social media has been so beneficial for marginalized groups, then why have their rates of depression increased since 2012 in the age of ubiquitous social media? In previous posts, I found that increases in teen depression were similar across racial and ethnic groups and across socioeconomic status.

It seems unlikely that the increase in U.S. Black and Hispanic teens’ depression was due to shifts in the political climate: The surge in teen depression began as Obama was about to be elected to a second term, well before Trump took office in 2017. Plus, several indicators suggest improvements for Black and Hispanic kids over this time. For example, the poverty rate for Black children and teens declined sharply between 2010 and 2022 (see Figure 3.16 in Generations), and Hispanic teens increasingly went to college (see Figure 4.31 in Generations).

Admittedly, those trends don’t capture individual links between social media use and depression. For example, are teens more (or less) likely to be depressed if they spend more time on social media? If marginalized teens benefited from social media, more social media use should mean less depression.

As some researchers have pointed out, most studies of teens and social media have used samples that are mostly White. It’s important to see if links between social media use and depression hold across racial and ethnic groups.

One of the best places to do that is in data from Monitoring the Future, which collects a large, nationally representative sample of U.S. teens every year. Since 2018, the survey has asked 8th and 10th graders how many hours a day they spend using social media and had them complete a 6-item scale measuring symptoms of depression. Since social media use tends to be more problematic among girls, I’ll focus on girls here.

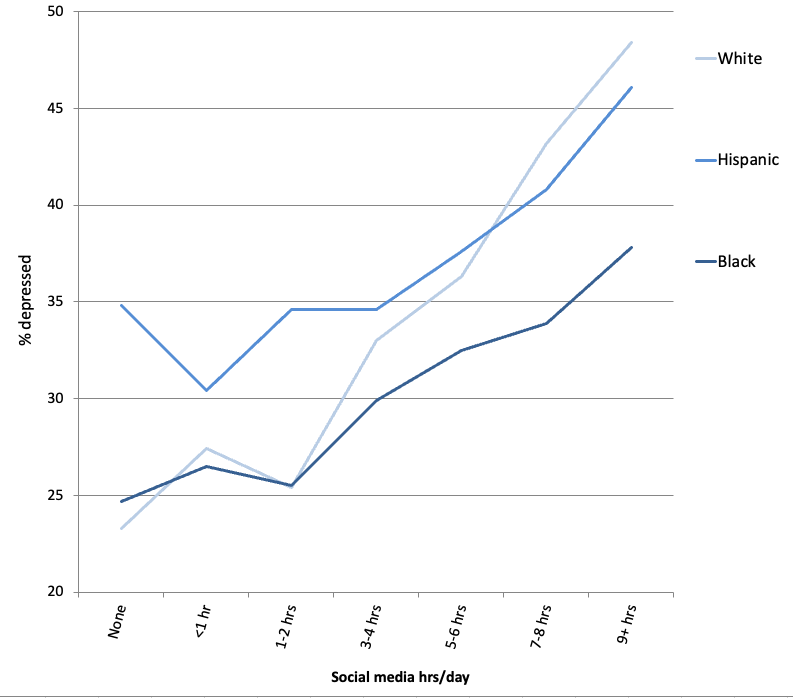

The results are straightforward: Heavy users of social media are more likely to be depressed than light users regardless of race or ethnicity – the link appears among Black, Hispanic, and White teen girls (see Figure 1). This is exactly the opposite of what you’d expect if teens in marginalized groups (in this case, Black and Hispanic teens) benefited from more social media use. So: The risks of social media use — especially heavy social media use — still outweigh the benefits, even in marginalized groups.

Figure 1: Hours per day using social media and depression, by race and ethnicity, 8th and 10th grade girls, U.S. Data source: Monitoring the Future. NOTES: Data collected 2018-2023. Controls for grade, mother’s educational attainment, and 6-item composite of time spent with friends in person. Depressive symptoms are measured with 6 items on a 5-point Likert scale; an average score of 3 or above counts as depressed.

Race does moderate the link, though: rates of depression rise faster with more hours of use among White girls than Black girls. However, Black girls are also twice as likely to be heavy users of social media than White girls, as I showed in a previous post. Thus, a higher percentage of Black girls are both heavy users of social media (7+ hrs/day) and depressed (15%) than among White girls (7%). Thus, a higher percentage of Black girls than White girls are negatively impacted by heavy social media use, mostly because more Black girls are heavy users.

It’s also notable that Black girls who don’t use social media at all have the lowest rates of depression — not what you’d expect if social media had clear benefits in this group.

What about Hispanic girls? Just as among Black and White girls, Hispanic girls who are heavy users of social media are more likely to be depressed than light users. But Hispanic girls who are light users have higher rates of depression than Black or White girls in this category (see Figure 1, previously). That produces a smaller difference in depression between light users and heavy users among Hispanic girls. Hispanic girls’ overall higher rate of depression blunts the association with heavy social media use, but it’s still very much there.

That said, the less pronounced association between social media time and depression among Black and Hispanic girls deserves attention. Are they using social media in a different way from White girls? Are they less likely to develop body image issues from using social media? Are they more likely to find a sense of community on social media? If the last is true, perhaps there are other ways Black and Hispanic teens can find community online apart from algorithmic social media.

Overall, though, there appear to be more risks than benefits for heavy social media use regardless of race or ethnicity. Some have argued that policies reducing the amount of time teens spend on social media would harm racially marginalized teens. Based on this data, that’s unlikely to be true. Instead, reducing social media time would likely benefit them, especially as more Black and Hispanic teens are very heavy users.

The bottom line: Spending more than 7 hours a day on social media benefits no one – except the executives of the social media companies.

Thank you for your commitment to evidence based research. I often hear psychotherapy clients (and others) state that social media is helpful for marginalized groups. They hold this view because it makes sense to them, not because they can back it up with empirical data. Clearly, marginalized groups need safe places to find support (as we all do), but your research and writing challenges us to think more carefully about how this might be done.